Mondo Decay is a photography book and music project

Brad Feuerhelm, Mondo Decay

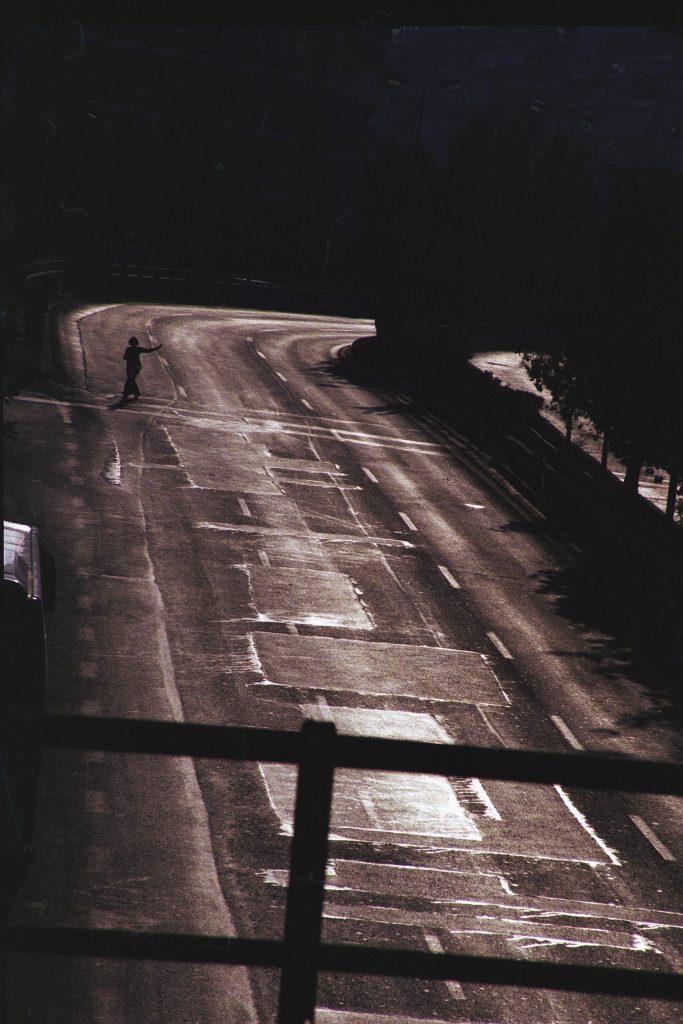

Mondo Decay focuses the group’s critical practice on the genre of horror itself, most notably the troubling sights and sounds of 60s and 70s Italian Mondo, cannibal and zombie exploitation films by Gualtiero Jacopetti, Umberto Lenzi, and Lucio Fulci. Instead of the “savage” tropical climes as employed by the genre’s directors, the exoticism found in original Mondo films has been subverted to look at the failings of capitalism in the West.

Brad Feuerhelm, Mondo Decay

In the process, the duo summon an array of experimental techniques borrowed from the likes of tape music vanguard Halim El-Dabh, Vladimir Ussachevsky and Delia Derbyshire; dub and bass culture innovators King Tubby and Scientist; and Houston dance music and rap pioneers Darryl Scott and DJ Screw, drawing a line of inquiry into the musical concept of decay. By embracing the same antiquated resources—various tape recorders, tape echoes, low-bit-rate samplers, and short wave radio equipment—Tesche and Mahan explore the deterioration and abstraction of Feuerhelm’s imagery through decaying frequencies, phrases, and recording mediums.

Contributions from the Pop Group’s Mark Stewart; Chicago no-wave industrial gospel godfathers ONO; Cleveland, Ohio’s genre and gender non-conforming Black Culture amalgam Mourning [A] BLKstar; renowned authors Blake Butler, Sohail Daulatzai and Michael Salu; Brazil-born, Berlin-based visual artist Luiza Prado; and musician/designer Farbod Kokabi, give voice to the sound of future-oriented de-colonial subjectivity and help to further realize the anxiety-fueled, pandemic-induced isolationism roaming throughout the album’s cinematic 48-minutes.

Mondo Decay, purports to flip the lens on what is exotic now and what life feels like under the extended lockdown and oppressive moment.

Brad Feuerhelm, Mondo Decay

One of the frustrating paradoxes of the exploitation films of the ‘70s and ‘80s is that, though they can often be problematic and disturbing, they also have killer soundtracks. When Lee Tesche and Ryan Mahan of radical rock band Algiers, and photographer and drummer Brad Feuerhelm, began working on their new project, Nun Gun, they decided to face both of those aspects head on.

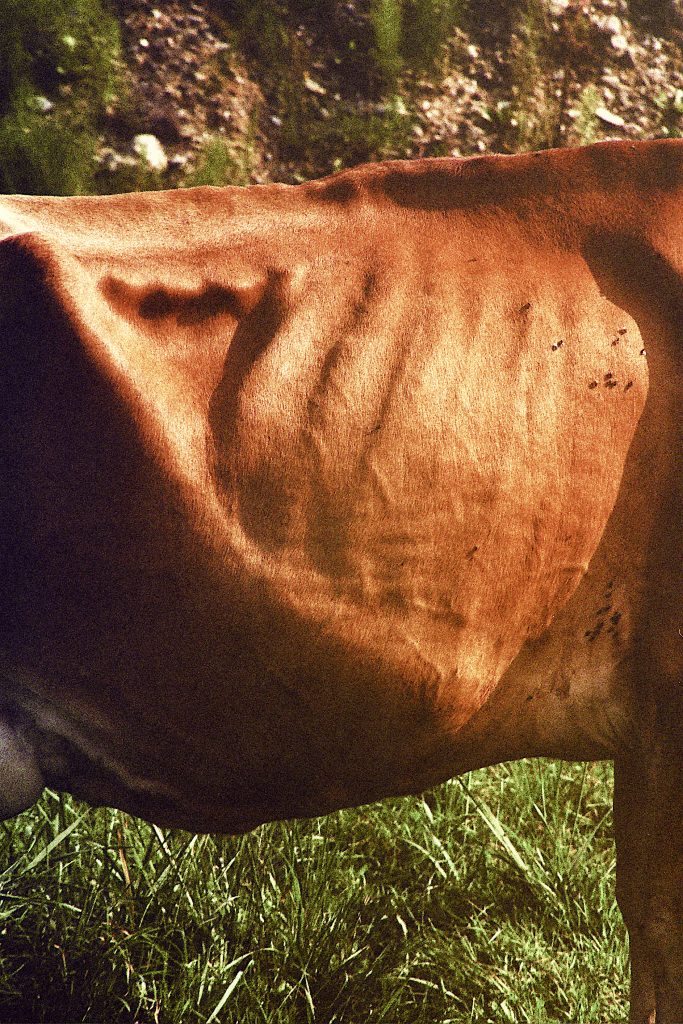

“If you look at when these films were being made,” Mahan says, “they were reimposing notions of savagery and periphery versus ‘white innocence’ at a time when colonialism—like, actual existing colonialism—was still taking place.” He points to the Wars of Independence in Angola and Mozambique during the ‘70s as one particularly notable example. With Mondo Decay, the group’s debut LP, Nun Gun deliberately subvert those tropes. They pair pummeling, soundtrack-influenced synth music with Feuerhelm’s apocalyptic photography—most of which was taken in Greece—to demonstrate the failings of Western capitalism through a horror film framework.

The idea for Nun Gun began in London in 2013, when Feuerhelm received a copy of the soundtrack for Roberto Donati’s Cannibal Ferox. He brought it over to Tesche’s apartment, and the two ended up binge-listening to it. “It sounded fucking awesome,” Feuerhelm says. The next day, however, they realized they had been playing it at the wrong speed—they’d accidentally listened to it slowed down. “We played it at the regular speed,” says Tesche, “and it wasn’t as menacing.” The two decided that, at some point, they would create their own slowed-down horror score.

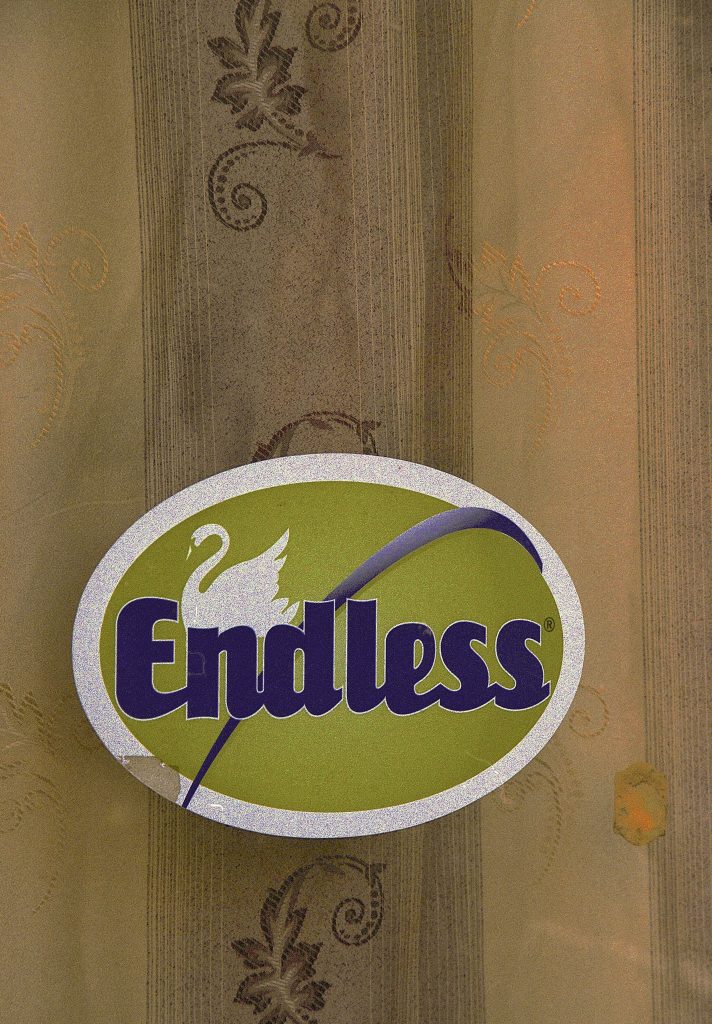

It took a while to materialize. In fact, Feuerhelm’s visuals for Mondo Decay preceded the music, coming together between the end of 2018 and beginning of 2019. Films like Cannibal Ferox cast a repulsively condescending lens on indigenous populations; Feuerhelm’s photographs do the same to Eurocentric imagery, especially in a place like Athens, the “birthplace of democracy.” The photos consider the idea of abjection—a fascination Feuerhelm attributes to his time in Catholic school—and its links to metal, industrial, and horror “You can’t dissociate seeing someone naked, bleeding on a cross above an altar from the abject state of how you look at or listen to metal,” he says. Feuerhelm extends abjection beyond the organic, finding it in the signposts of Athens, itself. Rust, dust, detritus, broken toys, trash, malfunctioning digital signs—the darker corners of Athens host tributes to failed Western relics and saints. Other photographs draw on the history of film—a sunbather becomes a nod to Antonioni’s Blow Up; a sign labelled “Kino” suggests the international film distributor of the same name. When Tesche saw Feuerhelm’s photographs, he immediately wanted to provide the soundtrack, and asked his Algiers bandmate Mahan to join.

Mondo Decay’s very specific sound is due to Nun Gun’s self-described “goth & screwed” technique—write & record at regular speed, bounce the digital files to tape, then manipulate and slow down the tape, and bounce it back to digital. That’s where the album gets its brooding, industrial atmosphere, which imparts a sense of the uncanny. Despite the uniform production technique, Mondo Decay covers a lot of stylistic ground: The seething, synthwave opener “The Spectre,” features writer, editor, visual artist extraordinaire Michael Salu lamenting the stagnancy and banality of decline: “Time melted, the formulation of days grew meaningless.” The influence of DJ Screw is particularly apparent on the swampy hip-hop number “The Aesthetics of Hunger,” and on the kinetic “Stealth Empire,” Mark Stewart of the foundational dubby, post-punk band The Pop Group, examines the specific anxiety, uncertainty, and culture of mistreatment inherent in Western capitalist society: “Instability, unpredictability, enhanced reality, harass, coerce, cajole, the manipulative settings of control,” he declares, going on to call out “ambient abuse” and “abuse by proxy.”

In addition to Stewart, Mondo Decay features an iron-clad group of guests, all of whom create art that operates from a place of anticolonialism: from Cleveland soul voyagers Mourning [A] BLKstar; to P Michael and travis of industrial gospel band ONO; and Geographic North co-founder Farbod Kokabi, who voices the album’s poppiest song, “On Neurath’s Boat.” The song is undeniably catchy, and Kokabi’s theatrical, dynamic vocals steer the song. “I’m a huge Paul Haig [of post-punk band Josef K] fan,” he says, “and through the years, his intonation and refrains found a place in my own musical vocabulary, so I looked to that stuff for inspiration. It’s debatable whether or not you can hear it in the end product, but I suppose that’s the excitement—you never know how your influences will mix with your DNA.”

The album’s final track, “America Addio”—a play on the title of 1966 mondo film Africa Addio—begins with a slowed-down sample of Georgia Bea Jackson discussing American violence, before giving way to abrasive guitar, dirge-y synth and, eventually, sheets of noise. “I don’t need to talk about American violence,” Jackson says, “you can look all of the world and see American soldiers everywhere, fighting in other people’s countries and killing them.” It’s a haunting passage, and the fact that the song eschews drums or drum programming makes its words and message that much clearer. Exploitation films like Cannibal Holocaust disingenuously invite viewers to ask who the real “savages” in the story are, the capitalists or the cannibals. It’s a cheap move—an effort to save face after two hours of blatantly racist and misleading caricatures. On Mondo Decay, there’s no such cognitive dissonance—the sounds, the photos, the appearances, and the purpose behind them are clear as day.

Brad Feuerhelm, Mondo Decay