Crackle & Drag film still

Ericsson Interviewed by ASX. Crackle and drag.

By Brad Feuerhelm, May 2015

Ericsson’s reliquary and totemic works concern his mother who suicided. The experience left Ericsson to re-work his familial and maternal understanding. In this re-examination, he has made works from his mother’s ashes, which imbibe a hauntological sense of absence. In a way, it reasons that these works are a process of coming to terms with umbilical severance and the loss that accompanies one’s bond with his/her origins into the world. The abyss is never far away, but these works also become clear insights into memory, biological dialectic conversations, and the nuanced examination of self under the duration of mourning.

BF: Having battled the early death of my own mother as a significant milestone in my own life, coming across your images makes for some uncomfortable reverberations in my understanding of your work. The overwhelming feeling I can expand upon is that of loss, perhaps also of the need to remember?

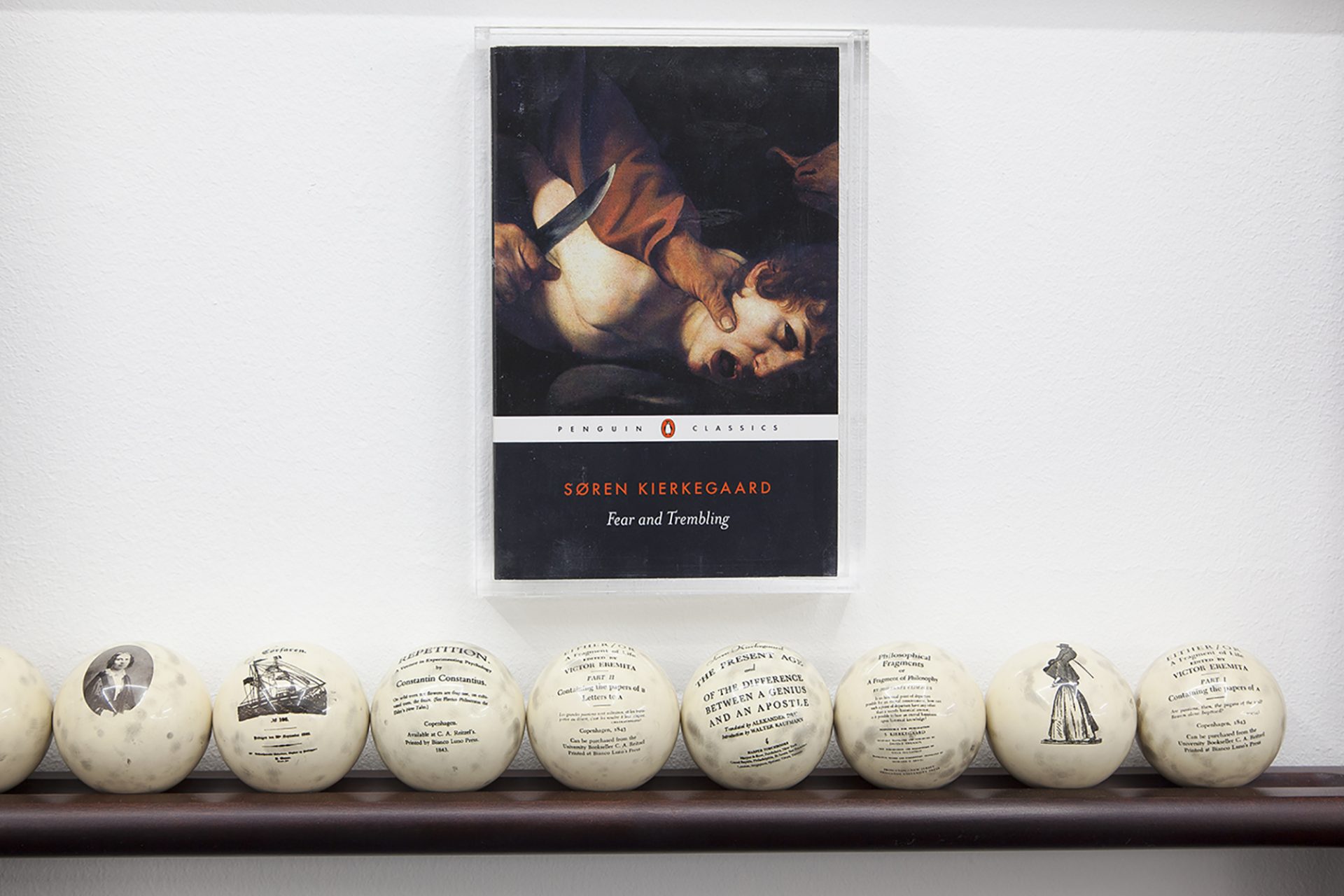

TE: I feel this same odd paradox all the time. The way these gestures engage others in their own private dialogues matters a lot to me. I don’t know about you but for me one of the initial traumas I experienced after my mother died was the odd callousness and even blunt stupidity of the “world” from hospitals, to funeral homes, to friends and family, and on and on, there was just no where to lay the grief down, no platform, no place. Added to that it was a suicide so the shift in reality was immediate. I ended up just driving all over the place in rental cars. Like being lost to the world myself like a dead person is was the most comfortable place to be. I remember being parked in a church lot in Ohio, I just drove in from NY and I stopped at the end of a street I had walked down so many times as a kid, revisiting that childhood spot at that moment I broke down in the car. Oddly a cop pulled over, no idea how he got there, maybe someone called him, I don’t know how long I was parked there but that moment with the cop, who I think was pretty nice about it, I didn’t open up to him or anything but I think he saw my grief was genuine and was cool about it, but that sort of odd gulf between the state I was in and the way the world just kept going, cops being cops, people just doing there thing, it really stood out to me as absurd, and it’s always like that it happens to people all the time, a hole opens up, usually it’s some sudden tragic thing like a death or an illness, but of course it can be a much worse thing too, look at this crazy earthquake in Nepal, 8,000 + people, how does that boil down to the living remaining individuals? Dropping out from the rest of the world in a personally tragic moment and seeing there was no place to be “off” “lost” or out of sync whatever you want to say, it infuriated me, you know the comments like “you have to get over this” stuff like that, well meaning friends trying to get your mind off it. One of the few comforting things someone said to me and he’s still a close friend today, was something like “if you are not fucked out of your mind at a moment like this, what are you thinking?” I didn’t want to get off it, I wanted to drill down into it, I was feeling this incredible gut level wordless possibility to actually get my head out of my ass and live right. I perfectly recall standing on a corner in Brooklyn wondering should I just blow up my life and take this crazy ride or should I try to keep things together. I even vividly recall watching a white pigeon land on a spare tire on the back of a jeep and I thought it was a sign, the bird and the tire, grief does something to the mind, and so I did blow up my life, I let everything go to hell and what wasn’t already falling apart I pushed it to fall apart. I let go of everything. I lost New York, my marriage fell apart, I dropped my art, I dropped my career, I went back to Ohio in a rental truck pretty much just filled with my books and moved in with a friend. Long story short and I’m still jaw to the floor amazed by all this but I did get my head out of my ass and I found in all the places I was either to afraid or to embarrassed to look the life I should be living. I stopped believing there was a right way to do something and just started doing it my way. I really think this was my mother’s gift to me, the gift of death as Derrida says. I woke up. So in a nutshell I think my work is two pronged in this way, meaning my desire to put the work out there to a “public” which of course is an assortment of unique individuals. But the two prongs are one for the public a, real active and energetic “fuck you” to the sleepwalking majority that never wants to look at the ugly stuff, divorce, suicide, illness, addiction, depression, anxiety, bereavement, racism, you name it, the majority seem to try and avoid it, even though our lives, their lives, are filled with these complexities everyday, and then more gently, more idealistically it’s an invitation to that rare individual that might see the possibility I found in my life in their own life, maybe wake up to themselves like what happened to me. Start to live; start to see how you can be dead and alive at the same time instead of alive and alive. Pain, loss, grief, for me are not passive things or things that put you out or down, their active things that bring forth new possibilities, unimaginable things. My life became my work, simple as that. It’s crazy but at the time I had been reading Kierkegaard for years and this was the main thing I got from him, don’t think, live. People die from just thinking, they die thinking things that can’t be thought, especially the question “how to live?” you can’t answer that intellectually, it has to be lived.

BF: You have chosen to use fire in an almost ritualistic way throughout the work…you have burned an image of your mother in an almost iconoclastic metaphor, was this in an attempt to burn away the notion of memory or was it to place emphasis on the crematory history of your mother’s remains? Can you expand upon your use of fire and smoke as seen through the nicotine portraits?

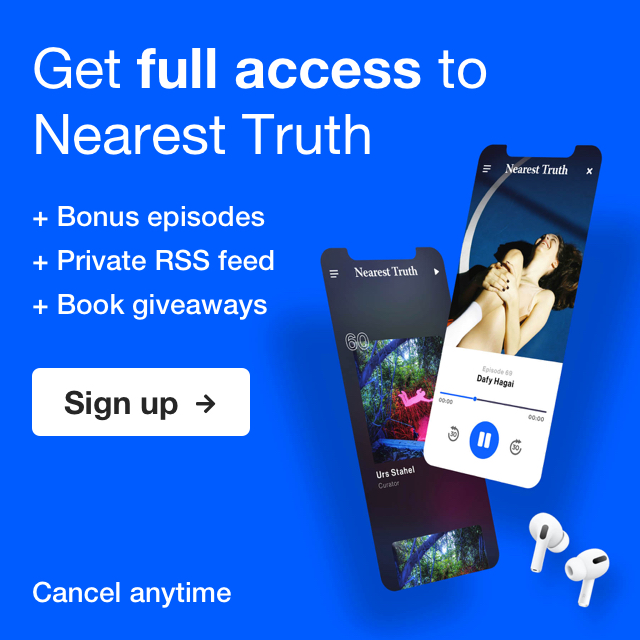

TE: As a kid I was usually at either of my mothers parents houses after school. Both houses had fireplaces in them going all the time. Both of their driveways were filled with logs and downed branches. I spent hours each week splitting and piling wood and breaking up the smaller branches into kindling to put in the wood shed. Their fireplaces burned almost all year long, less in the summer. My grandfather lived alone and he was crazy about his fireplace, in late summer the woodpile was as high as the garage. Everyday after school and on Saturdays I split wood with him, either with sledgehammers and spikes or with a gas powered splitter that sounded like the end of the world. Every few years we’d take the mantle piece that surrounded his fireplace off the wall and repaint it. It would get so badly stained from the smoke. There were small burnt black craters all over his carpet where embers from the burning logs would pop and burn out. He lived in an old farmhouse on Euclid Avenue in Willoughby Ohio. It was a busy-ish street not far from the center of our small town. He sold books and antiques out of the house. Every inch of the place was filled with stuff. Old farm tools hammered to the walls, decorative plates, he had a player piano piled to the ceiling with piano rolls and of course books everywhere. As he got older he stopped painting the mantle piece. The flu in the chimney wasn’t working right and more and more smoke was drifting into the house. It would float and hang like gauzy ribbons throughout the front downstairs parlour. Sometimes it was so thick it stung my eyes and it was hard to breathe, it never seemed to bother my grandfather. Slowly over time the smoke stained everything, things nearer the fire were encrusted with black soot and no longer registered as anything but charred shapes, further from the fire things were stained a golden auburn or a faint yellow. Paintings and glass framed photographs that you could no longer see pictures inside of covered the walls, a set of Norman Rockwell plates near the ceiling showing the four seasons were all just black discs. I’d go to McDonalds with him for lunch and people would smell the fire on him and ask each other if they smelled something burning. Even his hair was smoke stained. In the end it killed him, the carbon monoxide poisoned his body and brain and he spent the last few years of his life in a nursing home a few towns over. His property was sold and the house was destroyed.

So there was the fireplace.

I also think about my mother’s smoking she was a chain smoker. I started smoking when I was 9 or 10. I was allowed to smoke in the house. When I was a teenager, because we could smoke there, all my friends hung out at my house. After I left and she got sick and her drinking got worse she spent most of her time in the dining room the ashtray always smouldering and filled with butts. Before she died her house was starting to resemble her fathers place, the nicotine drooled down the walls, the ceilings and floral wallpaper were stained a similar auburn brown that nothing could clean. I even tried to paint a Kilz primer over it all but the nicotine still came through.

Obviously these “fires” were formative. And probably influence my work in ways I don’t always understand.

I do remember talking to an artist in New York about all the stuff I kept of my mother’s and her parents after they died, he couldn’t relate at all and just laughed and said I should “burn it” It was a dumb conversation but that one thing stuck with me. I have a house in Ohio where I keep everything. There was just so much shit and it wasn’t as pleasant as I thought it would be to sift through it, it always left me feeling dirty, not dirty like you need a bath but dirty in a deeper soul crushing way, there was something inwardly grotesque about hanging on to everything and one day I just started burning things. At first I thought I’d burn just a few things maybe even pull them out of the fire and they’d be caught between somehow, but once the burning started the things just vanished, some things I pulled out and laid around the yard and photographed but mostly there was nothing left. I was continually amazed at how powerful the flames were, they just devoured everything, but it felt clean in the same deep place but in the opposite direction of the way the hoarding everything felt, so I kept burning more and more stuff. I still kept a lot but I burned a ton of things. There’s something in all this, something between the labor of keeping a fire going and the way it destroys things, the way it’s smoke can be poisonous, the way smoking a cigarette alone can be a moment of reflection, a burning fire is like that too you stare into it and dream, burning away time and poisoning your lungs and mind. I have a vivid memory of shovelling the ashes under the iron grate in the fireplace at my grandmothers, filling a metal bucket and throwing the ashes into the snow in the backyard, leaving these black dashes over the pure white snow. All the recycling and change, paper to ash, wood to ember, cinders and smoke. Fire is among other things certainly a transformative thing. A thing is and then it isn’t. But there’s warmth too, it keeps you warm. A book by Derrida was recently translated into English, it’s called Cinders. I’ve read it ten times and still can’t grasp the full meaning but I think I know what he means by cinders, he relates the cinder to the holocaust, the burned bodies, a cinder is at once the visible remainder of something no longer visible, it hovers in an unusual middle place between presence and absence, it’s a fragile thing right on the edge of breaking apart itself. I think it’s this cinder that answers your question, a lot of my work whether it’s cast in ash, or nicotine, or is purely photographic it all inhabits this zone between being and not being. A photograph can be an image of a dead person. More hovering, more loss captured in a fragile deteriorating piece of paper. And now the Crackle & Drag film, it’s such a perfect medium for this in between place, just light on a screen, however you project them in a flash the flickering images are just gone.

BF: You have used her ashes in work, am I correct? Is this therapeutic for you and how do you externalise to an audience the deep trauma of living so close to your work and her remains? It must be at once liberating and at once difficult to work with…

TE: It’s terrible. I always feel awful doing it. But I feel good having done it. The process is awful, scraping over her remains in the urn, sifting through them, powdering the surface of the panel or muslin, mixing them into the resin and carbon graphite. It’s a terrible process. But the end result is meaningful. There’s that same dirty/clean thing I described above. Bone fragments scratch the screen and leave empty marks on the substrate. Again it’s awful. I do feel like I’m crossing a line, something un-sacred about doing it, but then profoundly sacred in the end having done it. I mean our current funeral rituals are utterly ridiculous, right? That was another struggle, watching the machinery her body passed through when she was dead. It’s hard to imagine with so many of us overpopulating the globe how it could be otherwise. You’re put in a box, buried with a stone with your name on it. Your cremated and put in a tasteless jar and set on a mantle, what else. Death is just death, it’s pure absence. But our lives are an extraordinary energetic mess. To bury the remains in the left over images and artefacts was a sudden and intuitive thought. I almost felt like Oh no, am I really going to do this, sometimes your own work drives you somewhere you’re loathe to go. But I followed along. These picture/objects feel like a true sanctuary, they’re mobile, they move like life moves, they’re less inert, the energy and complexity of being alive is again hinted at, there’s a presence, an influence again, a relationship with others even strangers, a continuance, the story is alive, unburied, unburned. It’s the perfect way to confront the total annihilation I describe death to be above. It’s a small victory but a victory nonetheless.

BF: Barthes, in his “Mourning Diary” compiled after his own mother’s death seems at once eager to let go and make progress, but consistently returns to the fabric of her memory through objects, photographs, and materialised remnants of her person…within creating a content so close to her physicality was there ever a moment where you though…”fuck, how do I expand upon this…and will this somehow give me closure”…

TE: There’s no closure for me, no resolving anything. I think about it or I don’t but it always floats there, noticed or unnoticed but always felt, always a driving influence. There’s no closure because our turn, my turn is coming. I remember her brother saying to me in his brutal and yet sensitive way “you better get over this, you don’t have long either” that woke me up, I was only just 30 years old but he was right, how long before I was gone? In fact in persistently engaging these narratives the whole thing feels like it’s beginning to drift toward a kind of fictional reality. Even though I stick to certain basic facts, my own shifting perspective through time and the growing distance between the once living reality and now dead reality creates a deeper and deeper gulf that again sometimes seems to get filled with a sort of fictionalised reality, even if I think I am getting at a truth of some kind it’s certainly not the capital T truth that living this life is, there’s no grasping that, it washes over all of us like a tidal wave, trying to look back, the inaccuracies and loss of minute but essential data risks all sorts of seductive fictions coming forward, which is also why I like the blunt fact of her voice whether in recordings or letters, it holds this authentic complexity in it. The tidal wave is more present.

BF: Returning to the nicotine portraits, which I find incredibly haunting due to their de-materialized presence crafted from nicotine and base photographic image… the ephemeral element of the work…the potential instability of process….the medium itself…this physicality, was it intentional to metaphorically enable the natural digression of a body through its use or was it very specifically a trigger for a memory that you have of your mother?

TE: She was a smoker and haunted by her past and extremely loyal to the people she loved. This created a lot of stuckedness in her life, she didn’t go anywhere, she sat and smoked and talked on the phone and wrote letters to me. Nicotine is poison, so is looking back, that can be a kind of poison too, so it made sense to cast these images in a poisonous chemical. It also stripped the snapshot of its sentimentality, and lame universality, a narrative was present beyond the little boy among countless little boys in a Halloween costume, the boy became specified. I know there’s a love for vernacular found photos now, they’re cool, I get it, but they’re really sad to me, lost images, lost lives, no hope to be in any way accurately ensconced in their own narratives, just lost in the world and sold at flea markets. It’s awful somehow, it’s our fate, even the illustrious dead, we don’t know who they really were, what it felt like to stand in front of them really, and that’s another thing it’s not so much about a personal narrative, it is that, but it’s this feel thing that matters more to me, there’s a certain way I or anyone felt around my mother, despite all her fuckedupedness she was incredible warm and loving and non-judgmental, she took your side about everything with advise that always went like “oh screw all those people” “or there nuts, don’t listen to that shit” She could really get there with you, be there, pure generosity of spirit and engagement with another. I wish I were more like her that way, I try, but my own ambitions get in the way, she had no interest in being something in the world, there’s a power to that and a foolishness to ambition, always trying to accomplish something makes it hard to just be there, be there for someone, some thing or even present to yourself. I can do it for my daughter though. I remember when she was a new born, this incredible thing happened, I was looking down at her and gazing into her eyes, and suddenly I felt my mother’s gaze coming through me, the thing it hurt so bad to lose, a certain way she had of looking at me that communicated total attentiveness and compassion, I’ve never felt that from another person in my life ever and it wasn’t just me she did that to, but there it was behind my eyes coming through to my baby daughter, I’ll never forget that moment and the odd way the dead, the ones we really knew and loved so much inhabit us after they’re gone. It’s a silver lining to say the least.

BF: Can you elaborate on the process itself?

TE: I started with an almost doll like construction of her dining room, just a small box really. I was having my first solo show in New York and I wanted to make a portrait of her but without a visual representation of her and I wanted all the objects to be made with the things that she kept around her at the end of her life, so the question became how to make things, images, texts, whatever with material like cigarette smoke, or alcohol, or glass, etc, Eventually as these things go I broke my own rule and included images of her and I used stone and marble, some things that were not related to her life, but just heavy and funereal. The installation was also an early shot at film making, a soundtrack played in the gallery, only music, not her voice, like now, her voice was present but usually engraved into glass or stone. This is when the nicotines came about, on the floor of my garage in Ohio I built this little box and put a silkscreen above it, like a ceiling, with the simple idea that the smoke from the cigarettes I left lit and smouldering beneath it would filter up and stain the paper, so instead of squeegee and ink, I used smoke. I imagined her inward landscape sitting alone at the dining room table rubbing her finger over her bottom lip and staring ahead of her, I’d seen her do this a million times, I imagined her going over the details of her life and past, over and over again, and the smoke drifting upward, projecting the internalised visual past onto the ceiling, or in this case onto the paper.

BF: My own childhood is similarly from the Midwest and I also grew up under conditions of a messy home. My mother worked very long hours and seemed unable to clean the house, stop buying newspapers, magazines, coco-cola…I was surrounded by mess…this carries on into my own accumulation of books, photographs, material…. has this been something that has followed you in your own life?

TE: Yeah it has. I keep a pretty minimal and pristine environment. But it’s a lie, hidden out of site there is chaos and disorder everywhere, I’m always trying to get a handle on it. That paradox we spoke of earlier is in this too, letting go and destroying things while at the same time trying to preserve them. The whole concept of the archive is a whacky and convoluted concept to explore. It goes in so many directions at once. Simply put it’s impossible. Plus the accumulation happening in my own life, my daughter is accumulating her own history now and I’m trying to preserve that. It verges on a kind of compulsion. I hold onto things. I know our lives are fleeting things and it’s all going to burn out somehow but it’s a painful truth and I hold onto things I guess as away to assert their significance. That’s what an art museum is right? a repository of stored actions and artefacts. There’s an absurdity to it, I know, to care so much for dead things and dead people to the extent one begins to neglect the living side of the equation, this has been another line to walk for me, looking back the way I do, while trying to move forward. It seems to be working but it’s not without it’s dysfunctions either.

BF: We accumulate imagery of our family, ourselves, our lovers, and friends…within the masses of archival material you have brought to the surface…is there one totematic photograph or object that haunts you to handle within this archive and how do you feel about the representations of yourself seen through these images. The little boy in the Halloween costume has become the man who has to take the call from his father and preside over his mother’s corpse. Do you recognize your younger self? I lost the little boy when I suffered the umbilical severance…I no longer know that body…..

TE: Initially I would have said there is no single totemic image. But the more I think about it maybe there’s one or two. But they are really insignificant and uninteresting little snapshots. One is a picture of my mother late in life, there is such a perfect mixture of defiance and pain and energy in it that is just so her. It’s not by any means a great portrait of her and it’s a terrible photograph but somehow that stuff is in there and I do struggle with that image. There are a couple other images of her where I see her best qualities come foreword just by the expression on her face, her love and availability and engagement with others, that’s in a few equally bad snap shots and every time I see them everything comes to a stop. As far as the boy I was, like you, that’s lost to me too. I have no idea who he was outside of a few confused memories. When I think of that time, around the time the scarecrow picture was taken, I was 8 or so, my parents were going through a divorce. My mom and I left Tennessee in the middle of the night, left my father and drove back to Ohio. We had a packed station wagon and I remember telling her when it was ok to switch lanes, it was like a game we played she also taught me to spell antidisestablishmentarianism on the way, some obscure legal term, that was the other thing about her she was smart as hell, but didn’t really care about it either. I don’t know what all went wrong but when we got to Ohio her parents weren’t happy about the whole separation/divorce thing and we ended up staying at a hotel, a Harley House, off the freeway not far from her parents houses. The odd thing about that night at the hotel and I can’t explain this or figure out how it happened but The Tin Drum was on TV that night, the German film, I vividly recall a scene where the creepy kid playing Oscar is screaming in a hallway and breaking the glass out of all the surrounding windows with his mother collapsed out of sight behind a closed door. Oscar in the book is so horrified by the adult world he cripples himself in an effort to remain a child. My own mother was asleep in bed while I was watching the movie. And again I can’t imagine why I was watching that film. Or why it was even playing in a hotel in Ohio. I have other memories of televised deaths and suicides from that time, in hindsight it all seems like a morbid premonition or something. I saw a British film on TV one Saturday afternoon about a motorcycle gang, each member happily commits suicide and becomes some kind of zombie, it was a dumb B movie but it gave me nightmares for years, all I saw were these smiling faces, hanging themselves and driving off cliffs and drowning themselves, it was nuts.

BF: In the “ashes” series, can you explain the emotional process of working directly with the application of your mother’s ashes? Technically and emotionally, how were you able to fix the remains to the surface…it is as if there could be a new genesis or relationship body to body that would occur….

TE: I touched on the emotional side of the process, again, it’s not pleasant and I’m always glad when it’s done. Her ashes have hardened now and I scrape them out of the urn with a spoon, they’ve sifted through a strainer into a fine powder, the powder is sprinkled over the surface of the substrate and mixed with the resin and powdered graphite I use as the medium. The ashes beneath the screen on the surface of the substrate become embedded beneath the resin shell of the medium that is also combined with the ashes. Bone fragments get caught between the squeegee and the screen and register marks on the surface of the image. Or tiny bones underneath the screen show up as spots where the image doesn’t register. The medium pools in places and creates other blemishes in the image. It’s not a straightforward screen-printing process. The whole thing’s a macabre mess really, but somehow the results are very beautiful.

BF: How can one absolve the notion of “effectiveness” in creating a work of art so loaded with emotion…. when would you stop or know…”it is finished”?

TE: That’s tough. I am always eager to declare it over, that’s it, I’m through, even other people like to suggest it will have an end. But then it never seems to stop. I always think of a Samuel Beckett quote I read somewhere that I’ve frustratingly never been able to find again. But he said something like stick to the old stories, love, death and loss. It’s true everything else seems like novelty thoughts to me and that’s fine there’s room for fun and jokes and novelty in art but it eventually fizzles out, we’re all struggling with the same fundamental shit every day of our lives and it’s been going on since the beginning of time. We’re just weird animals, we don’t fly like a bird, or do what fish do exactly but we mourn and struggle and do violence to one another to seemingly no end. Any attempt to grasp what drives the human psyche seems worthwhile to me, and love, death and loss do drive us. Obviously Warhol has been an influence too. His screens of course, which I use too. But like Duchamp he’s tricky. All that glamour and pop and celebrity and superficiality that still drives the art market today is present in his work. But on a recent trip to Pittsburgh to the Andy Warhol museum it was incredible to see how his work is decaying. And to me it’s even more beautiful, death, as a concept was very alive in Warhol’s work. I saw one of his flowers at the Met, this huge silkscreen but the linen was deteriorating, the paint cracking. It was beautiful. Nothing’s ever finished. I wonder if there’s really any beginning or end to anything?

BF: When you say…”Our images are ghosts”…I completely understand…yet I am at odds to understand the power of the photographic object as a stand in for representation…. when I consider an image, even of my own mother…. my need for a relic, a dissonant note of memory to hold onto is completely charged within this piece of paper…yet I can no longer hear her voice, laughter, or understand her hair flowing in alive breeze…have you ever felt during this process that the ghost was quantifiable or were you able to understand the process of the image on the mind and memory as that of an abstract. Is your mother present for you when handling the archive material at this stage?

TE: I agree with you, the photographic object is a weak substitute, I love that you say “photographic object” that’s really an important distinction, I was showing someone a work of mine recently and they were looking at it as if it were purely a photograph, at first I didn’t understand what they were struggling with but it later occurred to me, that the work I did wasn’t a photograph it was an image of a photograph and that’s a different thing all together. So yeah, singularly a photographic object doesn’t conjure up her presence much at all, except in those few unusual snapshots I mentioned, but those are weird exceptions. As far as feeling her presence goes. I’ve been working on all of this since before she died, it all started around 2000, but only as recently as last year did I ever feel her presence in the work. And currently I feel it all the time. I did an installation at MOCA Cleveland for a group show called Dirge. The curator Megan Reich had been developing the show in her mind for many years and had recently lost her father, it was an amazing exhibition. I made a large photographic mural and displayed a collection of artefacts in a glass case. But by far the most powerful part of my installation was a letter she wrote to me, I mounted it in a plexi box and hung it over the mural. I made the work fast and was sort of just going through the nuts and bolts of putting it all together, but when I got to the museum and saw the work together for the first time the letter hit me like truck. I don’t know why. But I really felt her presence; it felt like we had done the work together, I could feel the way it felt to be with her when she was alive. That feeling comes over me all the time now. I was struggling with the book I did for the Cleveland Museum of Art recently, my wife Rose was looking through my designs on the computer and she said that I was “incriminating” everyone including myself. I knew what she meant and it started to bother me, that night a quote jumped in my head from my mother’s cookbook (she kept sayings and quotes in the front of one of her cookbooks) The line was from a TV series she watched when I was a kid called I, Claudius, it was a BBC thing that came over to America, but the line was “let all the evil that lurks in the mind hatch out” I ended up using that line in the prologue of the book. I also came across a typed text I made from a voice recording I made of her but later deleted. At the end of a miserable speech about her father she says, “I don’t care what you put in your book you can, it was a terrible life…” It was an amazing moment, again I was struggling with how painfully personal it was to put this all out there and out of nowhere this approval, from her. That text would have been from 2000 or so and the book she was talking about would have been a magazine I was doing but to find that when I did after having forgotten all about it was amazing. To answer your question more directly I would say its not one totemic image or moment but the long accumulation of images and moments, which pretty much is what our lives are right? Accumulations. It might be that this posthumous accumulation of works and gestures has almost built her back up again, I would get into some murky and mystical waters here but it’s hard to deny the genuine-ness of my feelings. My young daughter sees her image everywhere and refers to her as Grandma Susie; she’s always leaving little sparkling trinkets by pictures of her like little gifts. I remember when her death was very new I was reading a lot, I always seem to read when I’m lost. But I was reading the poet Rilke, he has a poem where he talks about holding on to the “difficult” It made sense to me. And I’ve done that, and it’s been hard but I think I’m beginning to see the value of it, the meaning. A thing changes by being looked at, studied, examined, works of art are like that, but so are we, it’s an incredible thing to be thought of, to hold something alive in your heart, even if it’s dead and gone, in some miraculous way it’s brought to life again.

BF: I have heard a few sound samples of your mother’s voice…in particular…the very difficult moment when she expresses her pain…the message…I can hear the smoking and age in her voice…the pain is present…. when you examine the medium of the voice…does it conjure up the same “weight” for you? Or do the videos, photographs, or documents carry more significance? Is it all flattened into one “movement” between psyche and object, one body?

TE: I was going to mention this in the text above; you said earlier that you could no longer hear your mother’s voice. I understand that. I don’t know why the memory of their voice goes away, I felt that more with my grandmother, my mothers mother, I loved her deeply and I lost the memory of her voice really quickly, I was baffled by that. But incredibly I have all these recordings of my mother’s voice. Her voice is more powerful than any image. I have a ribbon of her hair, there’s something more evocative there too. The sound of a voice is immovably personal, private, hearing it you are confronted with the fact of a person, images can be so ambiguous, misread, related to other images, some images tell a story but are visually uninteresting, there’s all this duplicity in images, but a singular voice, it just is, the complexity is that in it’s just is ness it’s so profoundly context less and meaningful but usually only to the one who knew that voice, unless the voice says something culturally earth shattering or something, but if the voice is just saying common things or personal things it wouldn’t mean much to anyone else, but what I’ve learned after making the film about my mother which is entirely driven by her voice is that if you provide a context for that voice the potency really comes out of it in a more universally resonate way, just like the potency of meeting and talking to a living person, you feel their complexity right away you feel how little you know one another, you like them or you don’t, whatever but their singularity stands before you and there it is. I think this fact maybe more than any other is what’s really brought her presence forth. Her voice has been playing in my ears now for more than a year as I’ve developed the film. The constant repetition has even brought out long gone feelings of aggravation, sort of humorous to recall at this distance, or on the flip side a terrible guilt, I always felt like I left her in the lurch, I went to NYC and got out of the whole mess and just left her afloat in a life we once navigated together, the pain of that is fresh again. The film is about 45 minutes and after a year of strenuous effort it became a simple poem of loss.. It was a nutty process but she emerges out of it. I’ve learned the best way to tell her story is to simply step aside and let her do it, that’s not as easy as it sounds, it takes a lot of ego to make a work of art, but it takes a lot of humility to step aside and let someone else’s story come alive in your work, it’s an odd collision of intentions.

BF: Duchamp is obviously a huge influence for you, from the breath to the Etant Donnes” study you have made with your wife…there is still sorrow and apprehension in you works, but there is also a hint at moving forward. You have your wife, family, and placing your breath in the vessel that you have…its carbon dioxide form at times humidly gesturing at its life before, depending on storage, suggests life for me more than loss or death. Could you potentially deal with these works as life-affirming over that of life loss?

TE: It’s insightful the way you frame the question. This “hint at moving forward” there’s no choice but to move forward, right? I think that’s what’s made the looking backward I’ve done and am doing so complex. Moving forward changes how you understand the past, and that shift in the way you understand the past further influences the future. The Etant Donnes work at the time felt like a breather for me, a fuck the past sort of gesture, sex, is so rooted in the present and that work initially had a lot to do with sex, or maybe more broadly the erotic, but sex and death have an interesting parallel relationship to one another. I remember a friend telling me about his father’s death and the incredible sex he had with his girlfriend that same night. Sex is being alive, but sex like death is complicated, we’ve all experienced that feeling of something being taken from us after sex, even good sex, and especially when your young and it’s new, you wonder what just happened, what is the responsibility now, what’s changed? Sex is also an invitation to lose yourself, the French describe a female orgasm as ”a little death” for a moment your dead the pleasure is so unintellectual and purely physical at it’s height, but there are other shades of responsibility, maybe after sex you now have to be more present in someone’s life. You don’t have to, you could get up and leave and that’s it and that happens all the time, sex can be just fun too I don’t think it always has to mean so much, but I think the seeds of losing yourself are always there heterosexual or homosexual, male or female it doesn’t matter. And that moment I describe when I decided to blow up my life, that was a sexy moment, let go, die to yourself and your life and become something else, somehow death can be a gateway to something sexy like that, it’s not just mournful. I felt this the second I heard that my mother died, there was this intense double feeling of terrible grief and yet an oncoming lightness and sense of possibility. After she died and I let go of everything I had to keep doing it over and over, I had to keep letting go, letting go of who I thought I was, suddenly you didn’t go to New York City to be an artist you went to Painesville Ohio you got down into your own dirt into your real self, you stopped being ashamed of your life, you did things that actually made you happy, you spent time with people you really cared about, you stopped trying to impress, I simply became who it was I always was anyway, Like the title of a book of interviews with David Foster Wallace “of course in the end you become yourself”. This is becoming a jumbled up mass of thoughts, I should stop, but yeah Duchamp he’s king, we all have to find a way to kill that guy, but he started it. “Fuck off” he seemed to say. It’s art because I say it is.