Hannah Darabi’s work is something of a salvage attempt in archival terms. Her work considers the bibliographic output of photographic material during the years of and following the Iranian revolution in which the last Shah was overthrown. She has assembled an incredible knowledge of the subject and has been able to travel a collection of Iranian photobooks from Tehran to France, Belgium among other countries. She has produced a lush photobook on the subject itself with Spector Books in Germany that functions as a catalog to the exhibition, but is a phenomenal resource that very few people could have assembled. She has spent time researching private collection, libraries and has met a number of the photographers who made these books during the period of 1979-1983. Many of the books that were made have an ephemeral quality not only featured in the content, but also their physical condition, which due to their origins and their political message did not always survive under the new regime, post-revolution.

There are many perspectives regarding the deposition of the monarchy and its effects are still spoken about today in parallel to Iran’s current theocratic political discourse. The upheaval was not bloodless and the customary picture that the West paints of Iran under the Ayatollah has been largely pursued with an agenda, which is secular, but also geo-political among many other factors. In current climes, there is an uncomfortable chill in the wind again as the savage bell of “nuclear program” is rung by outside forces such as America (whom hypocritically will leave the nuclear INF treaty this year) and Israel whose strongman laughingly came to a televised meeting once to discuss Iran’s enrichment program with a box of crayons and a piece of paper.

I have been lucky enough to speak via email interview with Hannah Darabi who was kind enough to answer questions about her work with the photobooks of post-revolutionary Iran and her practice in general. I would also like to take a moment to give a bit of praise to Spector Books whom I have been only familiar with in passing until last year. The company is based in Leipzig, Germany and are focused on putting out into the world incredible books which feature at the crossroads of photography, archive, political thought and art. I really have a deep appreciation for a company that can send me a copy of Hannah’s book along with a book called The object of Zionism (review forthcoming) and continually publish a grueling annual catalog of seminal works. Hats off. Also of note is a nod to Le Bal in Paris and FOMU in Antwerp for running this exhibition. It is refreshing and necessary in a time when our own European countries slide increasingly into turbulent populism.

BF: Our Western view of Iran is that it is a country of contradictions. At obvious points it supports a rule of law that is theocratic and is fairly quick to excise dissidence and controls its image in strangely incremental uses of propaganda. Of course, photography certainly plays into this. And on the other hand, you have the Iran of the people, the creative, industrious, technologically-invested and pioneering Iranian who questions the motives of their situation and also considers what began in 1979 as a completely earth-moving moment.

Your book Engehelab Street, a Revolution through Books: Iran 1979-1983 (Spector Books) is monumental. In the book, you have assembled a catalogue of precious and very hard to find photobooks and publications in which the condition of Iran of the time is presented in the courageous printed material assembled that though propaganda, discusses many sides and voices from the Revolution and its following years. Some of the titles are very stark and graphic, horror and ennui fill the pages. And at times, some of the books, though still political, work almost as conceptual art-namely Began Boughoussian and Morteza Khanali’ s The Epic of the Revolution 1979 and also When the Walls Speak out by Said.

Your practice has its roots in photography. You studied in Tehran and according to your introduction text spent time on Enghelab Street, where the bookstores had assembled printed material that featured in your own research. At what point did this assemblage become more than just reference material? In assembling the material, the content can also be construed as a political act, was this part of your work-to collect as practice?

HD: It’s nice that you find the book monumental, it’s for sure a step to understand the complexity of representing the history of this period in Iran, but also asking the question of efficiency of a photographic archive in delivering its historic context. Here, the book gathers my personal collection, but the fact that these books are published during or after the Iranian revolution of 1979, bring us to think about the photographic archives of this period. There has always been an important circulation of the images from the revolution, but which ones and in what form are the questions I had? As I wrote in the introduction text, it was one very iconic image of this time, which opened the door to the whole project-a picture of Ayatollah Khomeini, in a book (Allah Akbar) that was fully aware of it’s calling in making history, darkness and of course some light with the use of photography by narrating the story of the revolution. What is also interesting is that the book allows us to comprehend the ideological point of view of its author, something that is not detectable in the image itself.

While collecting these books I tried to put together the maximum variety of photo books in all forms, the ones who represent the work of known documentary photographers of the time like Days of Blood, Days of Fire, or Riot, those who use the photography to communicate a specific massage, like The Tulip Revolution, and finally those who could be treated as artist’s book, like the two titles that you mentioned. At first it started with a curiosity towards the photo books published in Iran, but then it transformed to the urge of apprehending this special moment that encouraged not only the artists, but other people to make photobooks. Of course the culture of self-publishing existed in Iran, but mostly for political textbooks. The « White Covers » were published long before the revolution of 1979, but the interest in photobooks is specific to 1979 and thereafter. So I can say that it was also the collection itself, which established some of the ground rules of the project.

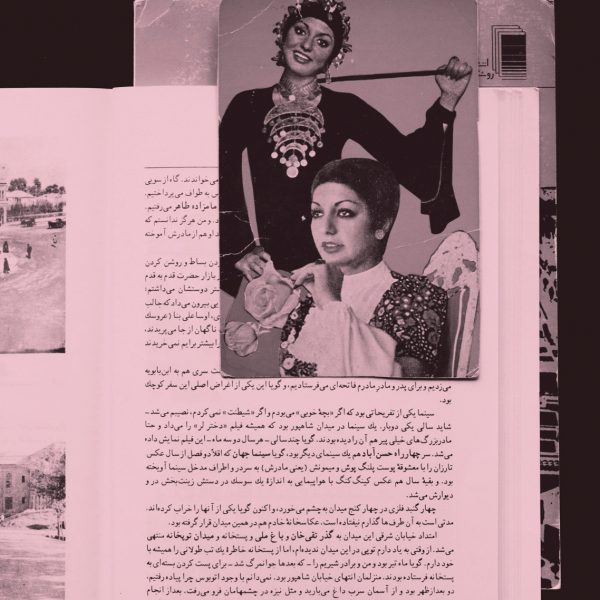

The third chapter of the book is actually my « manifesto » in response to these books. Here, my intention is to offer a new reading of this collection, and not to replace the ideas behind the books with mine in favour of one political way of thinking or another. These books propose a very fragmented image of one specific moment of history, the same moment that me and my generation had to deal with while growing up. By putting the pages of these books in conversation with contemporary images of Tehran (the town I grew up in), the publicity images or postcard which represent the pop culture, the family photos and finally the screen shots from Iranian cinema or tv, I seek to fill some of these gaps. The only way for me to relate to these books was to give them a new life in relation to my own living experience growing up in Iran.

BF: In considering the overall narratives that archives enable, we are left with interesting questions about how they are used at a later date. I remember reading your text about the single photograph of Ayatollah Khomeini and found myself thinking how differently a single photograph can be interpreted globally in the present from its inception in the past. When you were researching the material that you found, did you work in state archives and or other personal collections? You make some references to the books that you have in that you mention that some of the photographers themselves do not own copies at present.

A second part to that question also deals with your work and how you personally visualize what an archive is. I sense that you see the landscape as an archive to not only be documented, but as a living and changing thing-an environmental archive as it were. When you put that into perspective and the way in which photography functions to “slice” a segment of time from the world, this becomes an especially interesting idea about how to preserve a changing archive at a later date. In your own images, I would not be surprised if you saw the work as unfinished…in a state of flux. Can you give our audience some idea as to the conceptual rigor of how you personally see the archive as a format for production and what your thoughts are on its ability to be re-interpreted at a later date? We are speaking largely about images here, but we can keep this same inquiry to the photobook and the way in which its effect can expand and collapse meaning in a political, social or artistic manner…

HD: When I started collecting the books, naturally I needed to research the existing references on the subject, and unfortunately there weren’t that many. I found an article in one of the well-known Iranian art magazines about the Iran-Iraq war photography and a selection of books which have been published on the subject. I did some browsing on the national library search engine, which gave me some idea of the existing titles, but not enough. Later on I understood that there are two specialised libraries. « Howze Honari », an Islamic propaganda art institution, one on the subjects of the revolution of 79’ and the other is about the Iran-Iraq war. The books in these libraries have been donated by a collector whom I’ve met by chance and he informed me of the existence of these archives. These were the most complete archives on the subject among the public institutions. The collector in question, Mr Ferdowsi Zadeh, who had a very good knowledge of the books circulating in the book shops was very generous with sharing his information with me. He was a firm believer in Islamic Republic ideology and it’s leader Ayatollah Khomeiny. There is a short interview with him in the book where he outlines the reasons of why he is interested in collecting these books. So, my best resources had a bias for one particular ideology, and therefore their reading and interpretation of the books. It was legitimate to ask which books were not in these collections? For that reason it became essential to put the archive into a bigger historic context, the « White Covers » and the « Reconstructions » provide an alternative environment for the viewer. First, by pointing out the diversity of the point of views which resulted in the revolution that we won’t necessarily understand through the photos and the other by proposing another possible entry by putting them in conversation with other forms coming from Iranian visual culture and plays a role in the collective memory.

I find your remark on « landscape as archive » interesting. It’s true that in this work, and specially in both exhibitions’ installations, all the images were on the same level, and it was important not to create a distinction between these different esthetic approaches through their representations. Of course, receiving time as a nonlinear element is part of the concept behind « Reconstructions », even though there is a chronological order to the chapters. The global structure of this part relies on a classical historical methodology, but going through the chapters, the image of certain events became more significant in relation to their present context rather than their former use in revealing the past. It was also important not to simply reduce these books to objects of desire in a museum, in addition to stressing the subjectivity of the collection itself.

BF: In regards to landscape as archive, I think we like to contain the idea of “information” to boxes, but in reality, the environment around us hosts a lot of information, both temporal and fixed-the geological archive being one long body of documentation stretched out over a very long period of time. It is very important to consider these aspects of “archival practice” I think. It is why an organization like Eyal Weizman’s group Forensic Architecture becomes exceedingly important in the interpretation of the landscape to discuss humanitarian issues.

I also wanted to ask about your connections to the other artists involved in the books. Do you have close connections to many of them? Were you interested in recording their experience of making the books or did you conduct interviews by chance? I see some references within the text about each book that indicates that you certainly had experience with the photographer…

HD: Bahman Jalali who has the largest number of books in this collection was my professor in University of Tehran and surprisingly never showed these amazing books to the students. It became a question for me-why was it that at some point this knowledge of bookmaking has been lost and had not passed on to the next generation? I conducted some interviews (some are published in the book) with the people who were involved in the process of making or distributing the books. They offer a oral history of this period, but unfortunately we had to shorten the interviews and skip the information which was not directly about the books. As there is a lack of references on this particular subject, it gave me the opportunity to meet with people and this also helped with the research of the subject.

BF: If I had to guess about this aspect of a loss of material tradition as it relates to making books, I would say that it is a product of the times we live in. The disconnect between generations with the distribution of media and information becoming digital has probably created a divide in which the older generation probably does not think it is applicable and also the younger generation is probably mostly out of touch with material acts/protests/ and manifestations of material political culture-this is a huge shame because what is assembled in physical form tends to have a longer attention span placed upon it than 2 minute easily-forgotten articles.

This raises interesting questions about the physical nature of the book you have made. I want to ask a very basic question about how your book has been received in the greater Middle East. I know you have shown the work at Le Bal in Paris and FOMU in Antwerp. Has the work been shown in Iran or the Middle East in general, or have attempts been made to do so and what have been the reactions of people in Iran regarding the book itself? I suspect the academics are very interested, but how do your parents generation interact with the idea and finally how does the younger generation interact with the book and general concept of it? Are there large obstacles in exhibiting this work in Iran? What would they be?

HD: That’s true, I’m from the generation who experienced the beginning of the Internet and witnessed this de-materialization. But in post-revolution Iranian society there are other factors, which created this gap. The “trauma” resulting from the violence during and after the revolution plunged many people into silence. When the people who lived those days look at the book, or visit the exhibition, they often tell me how painful is for them to see these images. I think these photos open this wound, which carries a sense of failure within, especially for those who idealized the 1979 revolution back then. Another element is the state’s censorship which prevents the flow of information and limit it to one selective and incomplete narrative.

Unfortunately, the work (as we showed it in Paris or Antwerp) couldn’t been shown in Iran, the book hasn’t been distributed neither although it could become an interesting source particularly as you mentioned for the academic use. One of the intentions in this project was to reveal the different aspects of the revolution, specially the ones that my generation wasn’t properly informed of by the public education. It was an exercise to put together the different narratives of one story, which are not necessarily in tune with the actual official version. When the younger people see the work, they are normally surprised and amazed by the existence of these books, I hope the book finds its way to those who are interested in Iran.

BF: I keep returning to the works of Kaveh Golestan or at least the books he also participated in. The work stands out for some reason. The book he made on the Iran-Iraq war with Alfred Yaghoubzadeh and Golestan’s Riot book are very dark and sensual in some respects, filled with an existential and close study of violence. His work reminds me of Don McCullin in many ways, but it also reminds me of Robert Capa’s old adage “If your pictures aren’t good, you are not close enough”.

I know that you have spoken to several of the photographers, but one thing I wanted to know, having not seen the exhibition, is whether or not you recorded testimony from the living photographers? Did you interview them or archive their oral history of their books and experiences? Did you film them at all when conducting research by chance? If so, do you have plans to work with that material. If not, was there a conscious decision to forgo those interviews? Did any of the photographers associated with the books in your project wish to decline involvement? If so, why?

HD: I agree with you, Golestan was obviously influenced by the Spanish Civil War photography, he even has his version of “The fallen soldier”.

I recorded the voices for the interviews, as I had very little time for the book and the show. But the project continues, there are other photographers that I would like to talk to, and yes, I might film them this time, depending on the outcome of the research. For this, I had no objection from the photographers but some of the people who I interviewed for their political activities at the time didn’t want to give an oral interview. That’s the reason we have three texts among the interviews, they believed that the information will get lost or distorted during the transcription and preferred to give their own texts. I did also some interviews that didn’t use, which often started as a very interesting conversation but the moment I pushed the recording button, they would censor themselves and even change entirely what they have said before.