Cécile Poimboeuf-Koizumi and I talk publishing and artist Iseei Suda amongst others topics such as the photobook market.

*****Please consider supporting this episode by making a donation*****

Episode 23:Cécile Poimboeuf-Koizumi is something of a firecracker in the world of photobook publishing. Her choice of artist and the extreme precision in which she delivers outstanding works of art in the form of a book can be seen as a vital and explosive expansion of the next generation of photobook publisher. Her enthusiasm and general interest in photography and her artists are felt heavily in the conversation as we spoke about her publishing house Chose Commune. I truly believe that Cécile and Chose Commune are the wave of the future of publishing with their considered and valued contributions to the medium.

In this episode we talk about many things. We speak about Issei Suda, but also the wider topics of publishing. I believe the book 78 published posthumously by Chose Commune will bring Suda’s brilliance to a much wider audience.

Book Review:Issei Suda 78

I have been trying to put my toe in the waters of Japanese photography for the past few months. I find the language of Japanese photography somewhat foreign and I have been hesitant to jump full into the investigation mostly as it relates to the extreme amount of material, but also that when I see book people embark on the tour of Japanese photobooks, they seem to come back completely infected and with much more room in their wallets, if not their shelves.

With Japanese photography, a number of great artists seem to make the international scene with some ease. Of course, there are the “masters” Daido Moriyama, Kikuji Kawada, Noboyoshi Araki and Masahisa Fukase’s legacies to consider as well as relative newcomers Rinko Kawauchi and Miho Kajioka who are redefining the male-dominated field.

With 78 by Issei Suda, a few things can be untied right away. For example, as many Japanese photobook enthusiasts will speculate, the title has little to do with Suda’s historically important body of work Fūshi kaden which was published in 1978. Instead, the book’s title relates to the number of images which were called personally by Chose Commune on a visit to Suda’s home after his death. The publisher was given access to many of his unpublished works and chose material as they came across it ignoring the need for an over-riding super structure to shoehorn the work into. This is important as it allows the works to be seen as more free from the constraints of needing a certain seriality that may have been seen as forced or imagined by the publisher after the artist’s death.

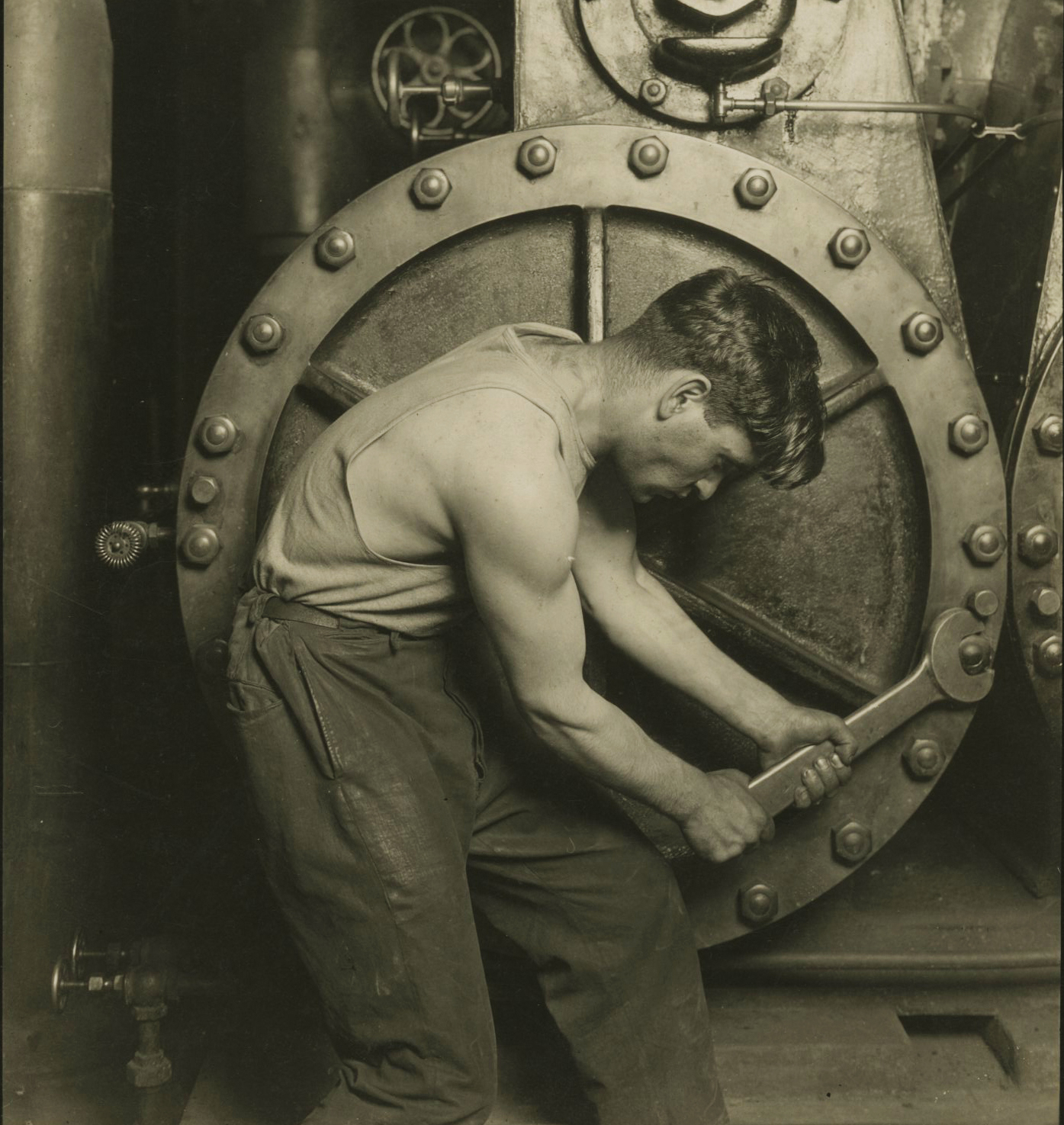

The images in the book are in this sense a pure reactionary selection by the publisher. One thing that I have noted previously having seen The Mechanical Retina On My Fingertips (Zenfoto, 2018) is Suda’s use of framing. Eschewing the traditional chaos of short and wide lenses used to embolden odd angles and casual snapping resulting in images that feel askew and disorienting as seen in some Japanese photography of the time, Suda is somehow more methodical and his interest in composition and balance, even in the context of “street” or “action” photography feels less chaotic, more considered. That is not to suggest that he did not share in the Japanese over-enthusiasm for making a great many pictures. I am also able to see that he had a good sense of how to photograph people, particularly children. The images are not over-sweetened, but they do feel thoughtful and feel somehow less dissociative than a number of his contemporaries images of subjects. Suda was a theatre photographer and you get the sense of his flair for capturing personalities in frame.

On a technical note, though the film stock also seems similar to his aforementioned contemporaries, Suda was also seemingly uninterested in entirely blasting out the frames and contrast with stark design qualities that are perhaps coupled with a post-war sensibility of radiated grit. There is an elegance underpinning his images more than ennui. One of the technical uses of pumping the contrast in Japanese photography results in an obliteration of person, place and becomes an atmospheric choice of condition and psyche. Conversely, with a book like Kerasu by Masahis Fukase, a similar employ is used in over-exposed printing. With Suda, he seems actively persuaded to let his images and not his techniques persuade the viewer of his ability. For the record, I am fine with all forms and drives, but somehow I find Suda refreshing and less ominous.

Again, I am still trying to feel out Japanese photography and Japanese photography books, but I can tell you that 78 is somehow magical. In a number of ways from the images inside the book to the production of those images in book form, the result is very considered, minimal and beautiful. There is zero gimmickry involved and it is perfectly designed for my liking, including the very smart cover design with minimal text placed perfectly. The crucial element that holds this opinion of mine is the use of the format and size of Chose Commune’s selection that emphasizes the different camera formats that Suda employed. Squares and rectangle co-habitate within the book due to the perfect measure of its size as an object. Nothing feels awkward or out of place leaving the viewer with an experience of deep rumination over the images themselves, which is perhaps the best elegy one could hope to inspire with Suda’s passing and his larger introduction to the West with 78.

It has my highest recommendation and will feature high on my end of year priorities.