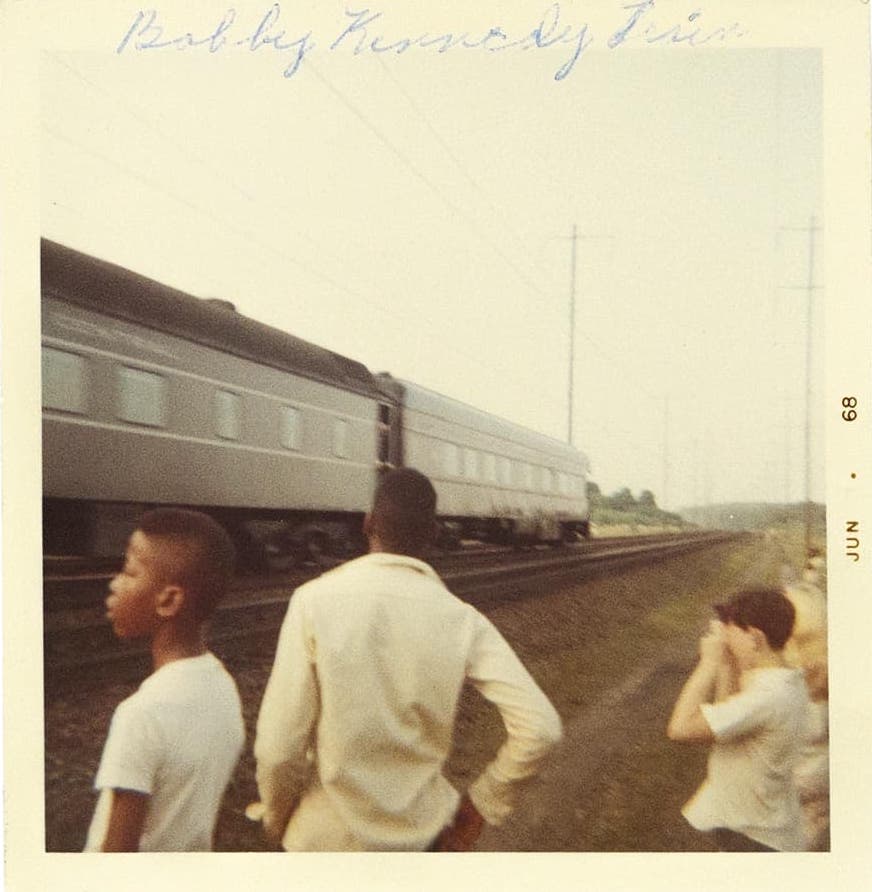

Ken Grant is a documentary photographer working in Britain.

*****Please consider supporting this episode by making a donation. every donation goes to bringing more episodes to light*****

Episode 38: Ken Grant‘s Benny Profane published by RRB Books absolutely floored me when I received it for review last year for American Suburb X. It was the book that led me to the British documentary tradition and reminded me that one single idea brilliantly executed can be career or genre defining.

Ken and I spoke about a number of things in this episode from Benny Profane to his work and thoughts on working in Britain and the change that has occurred over the past 30 years. We spoke particularly about how the docks have changed and how the way that a body of work like Benny Profane may not be made in current climes. Ken was affable and brilliant in his delivery of a general mediation about the state of photography and Britain as a whole. It was an episode that felt circular for me int he sense of getting to speak with someone whose work I did not know very well until his book came out, but whose work now feels very familiar for how close it sits to me on my shelves.

“The intrepid photographer, whether war photographer, journalist or documentary photographer believes their position to be in accord with the act of producing a record- his or her position to remain neutral so far as to let vultures eat at the doubled over haunches of starving children, to let the blood run from 96.8 to a syrupy and coagulating cold viscous matter on the pavements of Treblinka, Vietnam, Bosnia or Yemen”.

I often times consider the act of photography or the act of photographic investigation akin to trying to find a right angle on a lump of clay-its surface reluctant to be impressionable by my hand of authorship and its form lies in opposition to my intentions. The clay I believe, cannot impress upon me much either. I do not see the clay or the world around me as fashionable by my act of observation per se, but rather it is the act of impressionable observation from the position of the world/clay that forms and dents or manipulates my self, based on my ability to observe it. I am thus formed not by my will to become, but rather my will to observe external realities.

This is little doubt that the act of image-making and its observation are to be held responsible for the questionable states of any authorship. The subject, scene or image that is in front of the camera before the exposure is considered is the hammer or the rake forming this authorship. Defined by external pressures, the blows and rips of these pressures persist against the author and leave deep and cutting marks on his or her being. If I exist in a state unfettered by a forced internal dialogue with reason-I simply exist by proxy of external images. Fantasy is formed from the whimsy of the outside world, and myself such soft and indelible muddy clay is raked by its movements.

When we photograph the world, we are making selections. The intrepid photographer, whether war photographer, journalist or documentary photographer believes their position to be in accord with the act of producing a record- his or her position to remain neutral so far as to let vultures eat at the doubled over haunches of starving children, to let the blood run from 96.8 to a syrupy and coagulating cold viscous matter on the pavements of Treblinka, Vietnam, Bosnia or Yemen. These selections, though understandable in the court of ethics when regarding the economy of a photograph as absolute or as proof-enabling are beguiled by a sense of inhumane probability for the sake of neutrality. This is no doubt, apart from poly-amorous political party couplings between media spin, capitalism and political narcissicism why we have stumbled head long into the still black waters of the post-truth era. Photography’s duplicitous role as useful fabricator of result to either side of bi-partisan satisfaction is no doubt remarked upon in the now as something of the lark that it is-the generating machine of useful untruth.

Then there is the story of Ken Grant’s Benny Profane (RRB). It is an act of observance so utterly compelling in its throwaway subject matter that one cannot help but be a slight loss as to the “hows” and “whys” of its production and where Grant’s powers of observation stem from. Set in an incorrigible refuse heap in Birkenhead, North West England, Grant presents a story of what may have been deemed unobserved to us. He points his camera at a series of events unfolding, almost like an act of political will, in the least-likely of all stages-the city dump at Bidston Moss. Benny Profane is Grant’s inner mudlark and passionate observer brought to the surface, perhaps dented and bit raked by lived observations of history. What appears to be a comment on Thatcher’s Winter of Discontent has gestated within Grant and found a place nigh on 15 years later upon the trash heaps of Bidston Moss. The reason for its genesis is unclear-perhaps it is a strange homage to Liverpuddlian band of the same eponymous name whose lifespan lasted between 1985-1990, a convenient parallel to our timeline and geography. Outside of our geography, we find ourselves considering the role of Benny Profane in Thomas Pynchon’s book V, which I have not read, but will think about some day in paraphrased form when I take a picture of the next refuse pile that strikes my fancy. Grant admits that this heap is part of his own history, its image buried in his clay. What is clear is that this enmeshing of image and author can only have been produced from a very certain set of familiarities and observational tendencies thereof.

Indicative of our complicity in photography’s will to be impress upon, Grant wanders the bog, photographing people rummaging through the effects of the site, a stray pram set ablaze, which begs for a political analogy even if we refuse it the status of crumbling empire. Further, women are seen eyeing up the state of a perfectly good dress that has made its way to the smouldering festoon of civil rubbish management. We look and we feel the need for strong puncture-proof boots and we wonder, if inclined as to what is seen in such places. Like the final act of death, the decaying pits of rubbish are kept from site-they elicit an emotional condition of outrage and fear, no doubt harkening back to the black plague, the plague pits, and the pit of hades in which all three examples determine the living body’s right to refuse refuse. Benny Profane the band laid down a track entitled “Parasite” in 1988. I can’t help but want to make this an official soundtrack to this work. Grant is from Liverpool and so is/was Benny Profane. He would have been 21 at the time of the song’s release-chance, consequence or a mark upon clay? Another personal highlight of 2019 thus far! RRB has completely subverted my tendencies to disregard late 20th Century British photography. Their output is considered, deft and supremely important to showcasing poignant work. Well done! This is another for one for the 2019 list. Highest Recommended.