“Reading through them, I realised that the best ones seemed to create a kind of mental-image in my mind’s eye – which due to the tone of the text often took the form of a very deadpan, monotone, and even monochrome photograph of a little scene in small-town America; I was imagining a very straightforward picture made by Walker Evans or Lee Friedlander or Diane Arbus or others, of four dogs sitting on top of a car, or a guy standing next to a tree in the middle of the afternoon with bloody knuckles…”

Aaron Schuman is somewhat of a brother in Trans-Atlantic arms. Both of us hail from mid-sized towns in the nowhere of America. We come from 90’s and we have come to Europe engaged with the medium of photography. Aaron is graced with wearing several hats that range from writer, curator, artist and educator-all within photography. His new book Slant available through MACK feels somehow like a coming of age story where the protagonist finally gets the respect or in this case, the exposure for all of the hard work compiled over the preceding years. Slant is a very mature book. It plays with the authors past, the process of ageing while also trying to reconcile the nostalgias implicit with those pursuits. But the book itself is not so auto-didactic and more broadly speaks about the ways that we find ourselves at odds with images, text and media in the post-truth age. “Post-Truth Age”, words that had Burroughs himself uttered, I may still have rebelled against their weight and proximity to my own values. Aaron, ever the more civil of our pairing was kind enough to be interviewed about his work in Slant, but also about broader issues of being the inevitable prodigal son of Amherst, Massachusetts and the times in which Americans find themselves in the Trump era of acrimony politics.

BF: Thank you for answering a couple of questions. I appreciate you being able to enlighten our readers regarding your new book SLANT with MACK. Its been some time since we had a chat and it feels pertinent to effect a conversation about the book, which I am super excited to see published. MACK seems to be making large strides in selecting and publishing, alongside strong long-standing artists, artists just hitting their stride with incredible projects. You, John Lehr and Maja Daniels are all on the spring list and it is quite inspiring to see.

When you showed me a PDF of the work some time ago, I was really taken with the humor of the book, particularly the text pieces. Knowing your work in general, the use of monochrome felt new and very formal in a good way. I am having an ongoing discussion with Tim Carpenter about the use of the “formal” in photographic practice, but I would like to ask you about the switch. I am familiar mostly with your color work in the “American West”, so how did you come to choose black and white for this project? If I had to guess and I am probably wrong, it probably factors into the genesis of the series, which has to do with newsprint and news in general? Could you elaborate on the technical choice, but also give us some insight into how you came to make the work? I believe it starts somewhere with your dad sending you news clippings from Amherst?

AS: Yes – in a sense this project started in the summer of 2014, when I was visiting my parents for a few days in Amherst, Massachusetts. One morning, I was flipping through their local, weekly newspaper – the Amherst Bulletin – just to see if anything interesting was going on in town, and came across a page with the heading “Police Reports”. I started reading through them, and amongst the more generic and banal activities reported – fender benders, minor acts of vandalism, loud parties, and so on – I discovered several more unique, seemingly surreal and somewhat absurd reports of events (or non-events) that genuinely made me laugh out loud. For example, some of the first ones I found, which I took pictures of and posted on Facebook at the time, read:

“ANIMAL COMPLAINTS: 6:30 p.m. – Police took a report that four dogs were sitting on top of a vehicle parked on Pray Street. Police were unable to find the dog or vehicle.”

…or…

“SUSPICIOUS ACTIVITY: 1:13 p.m. – Police were unable to find a man who was reported punching a tree outside the downtown bars.”

They just seemed so ridiculous, and totally unworthy of media (or police) attention. And yet there they were on the printed page, being reported in this incredibly straight, deadpan, monotone style that seemed to imbue them with a real sense of authority, sincerity, seriousness, importance and newsworthiness – I thought they were amazing.

My dad was sitting in the living room with me, so I started to read some of them out loud, and he starting laughing as well – we spent about an hour doing this. After getting through that week’s page, I dug around their house finding back-issues of the same newspaper from previous weeks, and discovered that each week’s paper seemed to contain one or two gems when it came to the police reports. Reading through them, I realised that the best ones seemed to create a kind of mental-image in my mind’s eye – which due to the tone of the text often took the form of a very deadpan, monotone, and even monochrome photograph of a little scene in small-town America; I was imagining a very straightforward picture made by Walker Evans or Lee Friedlander or Diane Arbus or others, of four dogs sitting on top of a car, or a guy standing next to a tree in the middle of the afternoon with bloody knuckles – and that led me to think that there might be potential in terms of these reports becoming the foundations of photographic project.

That said, I didn’t make any real photographs at the time apart from a few iPhone snaps, as I was only there for a few days and busy with my family. But before I left, I asked my dad if he would cut out and save the “Police Reports” pages every week and send them to me in England (where I’ve been living for the last fifteen years), which he did. For the next four years, an overstuffed manila envelope would arrive at my house from time to time, filled with several month’s worth of police reports, which I’d spend a day or two combing through in the hopes of finding more that would spark photographic ideas.

So in a sense, your inkling that the black-and-white of the newspaper print itself pushed me toward choosing a monochrome photographic approach for this project is correct, but it was also the “black-and-white” tone of the police reports themselves that seemed to suggest a more direct, formal and monotone aesthetic. Very early on in the project, I did initially attempt to make pictures in both black-and-white and color, but quickly abandoned the color ones – they didn’t sit well with the texts at all, and felt almost too atmospheric, contrived and almost cinematic in comparison to the monochrome images.

In fact, the body of work you mention, which I made ten years ago – Once Upon a Time in the West – used color specifically and intentionally in order to invoke the cinematic and its relationship to the idea of the American landscape. That project – although it looks very “American” – was shot in southern Spain, on sets built by the Italian director, Sergio Leone, for the purposes of filming his 1970s “spaghetti Westerns”; in reality, nothing in those photographs is actually “American” (apart from me, behind the camera) and yet they seem entirely American, so much so that many people make the mistake of thinking I actually shot them in the American West. At the time, I was interested in exploring the possibilities of making work about America, and “of America”, but without actually photographing in the United States, and I discovered that by using cinematic visual tropes and pop-culture references that are generally associated with the commonly-shared image of America, such as those found in Westerns, I could create the illusion (and allusion) of America whilst never leaving Europe; and of course color played a hugely important role in this regard.

Actually, I think that movies (as well as television and advertising of course) – over the course of the last seventy years or so, since Hollywood’s widespread adoption of Technicolor onwards – are primarily responsible for the way in which we now all generally see, visually imagine, and aesthetically define America, and I sometime struggle to look at color photographs made in or about America without immediately associating them with the cinematic, which of course is often an artificial, heightened, commercialized or fictionalized recreation/reflection of America. Maybe this is why, at least when it comes to photography (and specifically so-called documentary photography of America), I tend to get very absorbed in black-and-white work – Evans, Frank, Friedlander, Arbus, Robert Adams, New Topographics and more recently Mark Steinmetz, Susan Lipper, Vanessa Winship, Gerry Johansson, Soth’s Songbook, Raymond Meeks, Adam Pape, etc. – in the sense that, with that filmic filter of color and its cinematic/commercial undertones stripped away, such work seems to offer access into another kind of insight into the country and culture at large, which is not necessarily related to commercial or cinematic reference points that have been deeply embedded in all of us via advertising, film, television, pop-culture and so on; somehow it seems to offer an alternative perspective, and one that is almost unique to photography.

(Speaking of the “cinematic” in photography, only a few weeks ago, I was putting together a lecture about SLANT, and wanted to discuss the (under)representation of New England in photographic history over the course of the last fifty years (something I’d love you to ask me more about later on if you’re interested) – I was inserting several color photographs by Crewdson to my Powerpoint, as many of his more famous works were also made in Massachusetts, only sixty miles or so west of Amherst, and I was thinking about the fact that when I was in my second year of college, I was interning at the gallery that then represented him in New York at the time – Luhring Augustine. Then all of a sudden a long-forgotten memory clicked in, and I vaguely remembered that one of the shows they had during my time there – and one of Crewdson’s earliest exhibitions – was a project that was very similar to his later work (in that it was staged, constructed, performed and so on), but was entirely in black-and-white. I quickly Googled it to check if my memory was playing tricks on me, but sure enough the dates matched – “Hover”, 1997 (https://www.luhringaugustine.com/exhibitions/gregory-crewdson2 ). I hadn’t seen that work for more than twenty years, but it was fascinating to compare these monochrome works to his later images, which are so saturated with a filmic color palette and cinematic effects, and consider the difference in feel, tone meaning, and interpretive possibilities between the two – furthermore, I was stunned to discover how these pictures resonated with those that I’d been making for the last three years, as seen in SLANT.)

That said, once I returned to England in 2014, I spent a long time – nearly two years – trying to get my head around how I might approach this work photographically. The clippings of the police reports kept arriving every few months, and they were so good; I quickly realised that in order to make photographs that would hold their own alongside the reports I would need to consider the complexity of working with text and image very carefully, and find an suitable way to make photographs so that I could eventually build a symbiotic relationship between the two. I started to research into American photographic history (and particularly photobook history), looking for precedents in which photographers had engaged with police reports, riffed off of written reports and newspaper journalism, and experimented with various ways to present found texts and their own photographs together. I ended up looking at things like:

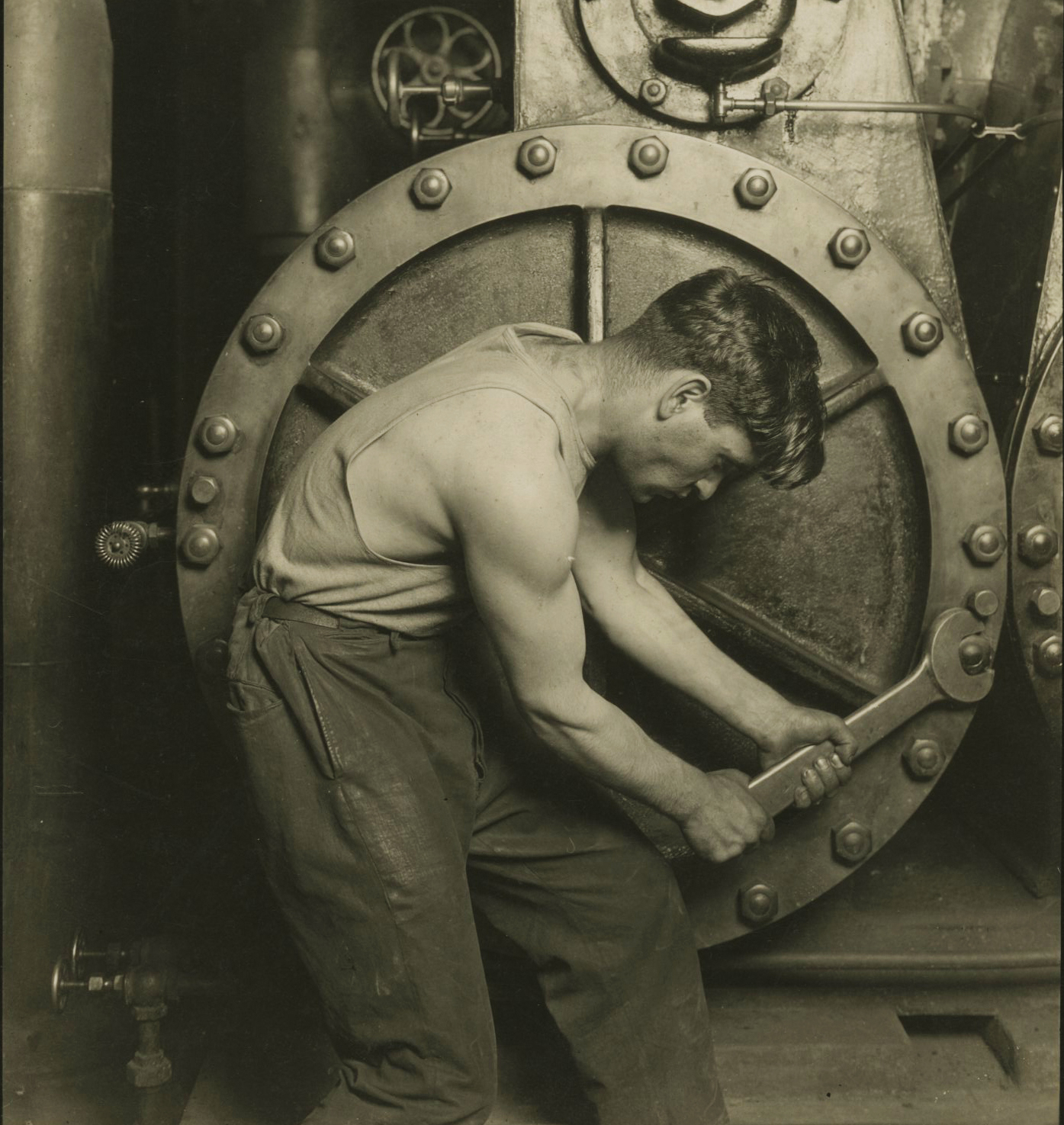

- Lewis Hine’s work from Ellis Island, in which he originally combined his photographs with succinctly written texts and quotes from poetry (https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-4e92-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99/book?parent=b0a962f0-c608-012f-b422-58d385a7bc34#page/1/mode/2up );

- Weegee’s Naked City, which incorporates tabloid-like captions and his own written accounts of events ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6OKozNy2CDQ );

- Bill Owens’s Suburbia, which pairs his photographs with short, edited quotes that Owens collected from his subjects ( https://vimeo.com/63070099 );

- Alec Soth and Brad Zellar’s LBM Dispatches, in which Soth and Zellar adopt the roles of newspaper photographer and reporter while traveling through small towns across the USA ( http://www.littlebrownmushroom.com/products/ohio/ );

- and much more…

Of course, many – in fact, most – of the precedents I was looking to for inspiration were in black-and-white, so it started to seem only natural to me that my project should adopt a similar aesthetic.

And then finally, what really set me on fire in terms of inspiration was a visit to the Paul Strand retrospective that opened at the V&A in the spring of 2019 (https://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/paul-strand-photography-and-film-for-the-20th-century ). In it, there was a vitrine that contained Time in New England (https://www.icp.org/browse/archive/objects/time-in-new-england ) – a collaboration between Strand and the writer and curator, Nancy Newhall, made between 1945-1950. I remembered the book from my high-school library – I’m sure I looked at it when I first got into photography as a teenager, and was in search of inspiration in terms of photographing what I considered at the time to be my very “boring” childhood surroundings – but I hadn’t seen it since. The vitrine allowed visitors to see only a couple, sample spreads from the book, so standing there I immediately bought a badly battered first-edition of it off of eBay for £10, and when it eventually arrived I was blown away; with my project in mind, it seemed almost too perfect.

In 1945, Strand and Newhall set out to make a book about New England, whereby over the next five years “Strand departed into New England with his cameras”, and “[Newhall] began ransacking libraries” in search of texts that reflected the “New England spirit”. Every few months they would meet, Strand would show Newhall his photographs, Newhall would show Strand the texts she’d found, and they’d try to find connection that would help bring the two elements together. The texts Newhall found were incredibly varied and broadly sourced – they included letters written by early colonial settlers, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Susan B. Anthony, folk tales and sea shanties, direct witness accounts of the Salem witch trials, the writings of W.E.B. Dubois and Henry David Thoreau, diary entries by Revolutionary soldiers and child millworkers, quotes from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, poems by Robert Frost and Emily Dickinson, and much more – even a diary entry by the minister and celebrated abolitionist, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, which begins: “May 19, 1886 – To Amherst to the funeral of that rare and strange creature, Emily Dickinson.”

Anyway, the ways in which Strand and Newhall cleverly interwove and built subtle relationships between his quite formal, direct and “straight”-laced photographs and this amazingly diverse collection of texts sourced by Newhall seemed to provide a lot answers for me going forward, both in terms of how I thought about making photographs in and around Amherst, and how I might begin to involve, connect and bounce them off the police reports.

“I returned to England in 2014, I spent a long time – nearly two years – trying to get my head around how I might approach this work photographically. The clippings of the police reports kept arriving every few months, and they were so good; I quickly realised that in order to make photographs that would hold their own alongside the reports I would need to consider the complexity of working with text and image very carefully, and find an suitable way to make photographs so that I could eventually build a symbiotic relationship between the two.”

For whatever reason, I think Paul Strand’s work has often been slightly overlooked by contemporary photographers (including myself) in terms of its importance within the history of American documentary practice – Walker Evans seems to have secured the “godfather” role in this regard, rather than Strand – and perhaps that’s due to quite explicit and overtly intentional “formalism” of Strand’s work, both in terms of its compositional and tonal execution (whereas “[Evans’s] eye can be called…anti-graphic, or at least anti-art-photographic”, as Lincoln Kirstein wrote in American Photographs (1938)…a book that also explores New England, and its colonial architecture in particular, rather thoroughly).

Looking at Time in New England, I realised that if I could go back to Amherst, but pull from the slightly differing early-20thC. “straight” approaches, aesthetics and philosophies of both Strand and Evans – somehow drawing from both the “formal” eye of Strand and the “anti-art-photographic” directness of Evans within my own photographs – and then could find a way to loosely fold in these very deadpan and contemporary police reports with care and consideration (as Newhall did with her found texts) so as to create newfound relationships and meanings, I might be onto something here. So in the summer of 2016, when I found myself back at my parents’ house again, I took my camera with me and felt that I finally had a real sense of focus, intention and purpose in terms making new photographs.

BF: That is a great amount to digest…Firstly, this makes more sense within the idea of the new book, the way in which you speak about the idea of the American landscape being tied to cinema or the unreal as it were for you is quite interesting and I hope that I am not digressing by speaking on it a bit.

The idea that America, and I do mean to reference the West particularly as you have mentioned, is now duly ingrained in our global psyche as cinematic and raises questions that are uncomfortable about the idea of programming the landscape and it is perhaps not so different with your work in SLANT as in a way, you are taking control of the Eastern seaboard and its small histories, perhaps specific to Amherst. The outcome is that perhaps the outright cinematic device is set down for the quasi-journalistic and perhaps we should discuss the transitions now occurring between the two, with cinema largely borrowing from “real life” docu-dramas-Narcos, Roma, etc and in turn, journalism/documentary is borrowing heavily from the cinematic-Richard Mosse, Alex Majoli etc…Its very strange to watch these borders become less definable in the current climate of not only political debate, but also the fear of a simulated dialogue revolving around technology in general…where does news begin and cinema end?

AS: I agree – our general understanding of the lines between news and cinema, or the journalistic and the fictional, are becoming increasingly blurred as we progress through the twenty-first century. Of course, we are both of a generation that went to high-school and college during the 1990s, and because of our fascination with images as well as our cultural curiosity, we grew up being intellectually inundated with notions of “postmodernism” and the late-Capitalist realization of “the simulacrum”, so this territory is pretty familiar to us, but we still come at it with a slightly critical or skeptical eye – i.e. we feel like we can remember a time when the “copy” or “simulation” was a reproduction of reality rather than the reality itself, and we romanticize that time and wonder if it wasn’t better, or more “true” or “real” than now.

It’s interesting: when I was in college remember my mind genuinely exploding when I was introduced to postmodernist theory, Baudrillard’s notion of the rise of the “simulacra”, and so on – it seemed so crazy, so scary, but somehow so terrifyingly accurate, especially to a nineteen-year-old in 1996. “…Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, whereas all of Los Angeles and the America that surrounds it are no longer real, but belong to the hyper-real order and to the order of simulation. It is no longer a question of a false representation of reality (ideology) but of concealing the fact that the real is no longer real.” Kaboom! But today, in 2019, when I sometimes find myself introducing these ideas to nineteen-year-olds at the university where I teach, the students hardly blink…they just look at me totally unfazed and are like, “And..?” It’s entirely second nature to them, and the idea that reality and reproductions/representations of reality were once two distinct, distinguishable, and separate things is the foreign concept. Anyway, I’m digressing and starting to sound like a dated old man, but the point I’m trying to make is that today it seems that news and cinema, or journalism and fictional narrative, are simply two sides of the same coin – one that serves as the currency for our contemporary interpretation, understanding and experience of reality.

That said, this is where the term “documentary” – or perhaps what you refer to as “quasi-journalistic”, which I love and find fascinating as a description – comes into play. Often “documentary” is misconstrued as a kind of synonym for “news” or “journalism”, but when John Grierson first coined the term in the 1920s – specifically in relation to cinema (in the journal, Cinema Quarterly) – he defined it as the “creative treatment of actuality” (realizing that this was quite a nuanced definition that could be easily misunderstood, he also admitted, “Documentary is a clumsy description, but let it stand.”) From the genre’s outset in the early-twentieth century, I feel that “documentary” has always been straddling the line between reportage and interpretation, accuracy and creativity, and fact and fiction.

Within photography in recent years, there’s been a lot of discussion about “expanded documentary” (Halpern), “speculative documentary” (Pinckers), “crooked documentary” (Soutter), and so on – which coincides with the rise of terms such as “alternative facts”, “fake news” and “post truth” with popular culture and widespread political debate – but “documentary” has by definition always been expanded, speculative and crooked in its approach. In Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), James Agee writes, “Isn’t every human being both a scientist and an artist; and in writing of human experience, isn’t there a good deal to be said for recognizing that fact and for using both methods?” And in a 1971 interview, Walker Evans stated, ““Documentary? That’s a very sophisticated and misleading word. And not really clear. You have to have a sophisticated ear to receive that word. The term should be documentary style.” Perhaps a better term is one taken up by writers: “non-fiction”. I love this term in the sense that it distances itself from the purely fictional, yet doesn’t claim to be entirely factual – it’s neither one nor the other; it says what it isn’t, but not what it is. If “documentary photography” were to be understood in a similar manner to “creative non-fiction” – think George Orwell’s Road to Wigan Pier, or Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, or any of the “New Journalists” of the 1960s-70s (Norman Mailer, Joan Didion, Hunter S. Thompson, etc.) – I think it would help to clear up a lot of misunderstandings when it comes to its relationship to and representation of “truth” or “reality”. Like creative non-fiction, documentary photography is and has always been a subjective, creative, interpretative, indirect, and nuanced response to reality rather than an attempt to reflect it with purity, objectivity and accuracy; and perhaps “the news” or “journalism” today – for better or worse – is shifting in a similar direction. In a sense, this takes me back to the Emily Dickinson poem that I include as a foreword in SLANT, which in many ways serves as a foundation for both my thinking and approach when it comes to both this particular project, and my current understanding of “documentary photography” at large:

“Tell all the truth

but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit

lies

Too bright for our

infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb

surprise

As Lightning to

the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must

dazzle gradually

Or every man

be blind —“

………………

BF: With SLANT, I was immediately drawn to the myth of Weegee before I had spotted him on the list in our conversation. Weegee, also in journalistic terms has some associative properties with Hollywood and the social landscape of America. It is also strange as what you are looking at with SLANT, if from a news stand-point, or quasi (not using fake yet)-news POV is the manufacturing of those associated images born from the word, not opposite, so in effect we find you manufacturing the romance of the language and geography into an image after reading the news. There is a display mechanism -an illustration of words or ideas exemplified after the fact that speaks on the culture or social life of Amherst.

I want to also rope in your book FOLK here because with you removing these news points and conditioning or producing a “record” or semi-object of document by way of photography, you are in some small way making a small ethnographic study. FOLK was a curious tale about how objects and their representations occur in archives etc and then how they occur when recorded again or rather in the “now” by an outsider. Perhaps that is a bit much, but I see some threads weaving in and out of SLANT that are tied to a few investigative ideas in your work.

“From the genre’s outset in the early-twentieth century, I feel that “documentary” has always been straddling the line between reportage and interpretation, accuracy and creativity, and fact and fiction.”

Do you want to elaborate a bit? Or disagree?

AS: It’s an interesting connection. I guess that in FOLK I was playing off the role of a particular, authoritative or “truth-telling” voice – in that case, the ethnographer or enthnographic curator – but loosening it up a bit to explore the more multi-layered interpretive possibilities of the information and material they gathered, as well as their methods for gathering, preserving and exhibiting it, by making that voice more open-ended and ambiguous (and potentially personal). Both the book and the exhibition came out of a collaboration with a respected institution – the Ethnographic Museum in Krakow – but as you note, my role was that of an “outsider”. On my first visit there, I was told that it was a museum of ‘folk culture’ or ‘peasant culture’, and my understanding of that was that it was dedicated to the preservation of the history, rituals, objects and culture of everyday people, and normal everyday life (rather than that of ruling aristocracies or grand historical narratives), which often throughout the museum’s history was sited by them in the surrounding small villages or rural areas rather than in the city itself. So in my own engagement with the museum, I adopted a similar seemingly “objective” social-scientific tone and approach, but treated the museum itself and its archives as the “village” that I was studying – and the curators and staff, both past and present, as its “villagers” – and then proceeded to “quasi-document” its everyday. This meant that I was drawn to what they considered the peripheral aspects of their museum – for example, I was often more interested in the boxes that housed their artefacts rather than the artefacts themselves, or the casual, end-of-roll photographs that the ethnographers took of each other on their field-trips rather than the formal photographs they had made of the rural environments and inhabitants – and the interpretive potential of these seemingly unimportant elements.

Similarly, in SLANT, I am exploring and playing off the role of the newspaper reporter – and the authoritative, “objective”, “truth-telling” voice of journalism – but trying to loosen it up by introducing some ambiguity, and focusing on what might be considered peripheral non-events rather than important news stories. Many of the police reports I include in the book compellingly, and with very specific detail in terms of time and place, tell the story of nothing really happening – “6:32 p.m. – A man described as having a ‘wild hairdo’ on a West Street porch was not located by police”; “6:36 a.m. -Strange sounds coming from the woods near Mill Valley Estates were determined to be trees creaking due to the cold temperatures”; “2:48 a.m. – …The woman later told police she thinks she may have been dreaming prior to calling 911” – and similarly the photographs, which are taken in a “straight” and rather matter-of-fact manner and feature very ordinary, everyday places and peripheral things, are seen in a new, strangely compelling and potentially meaningful light when considered alongside these kinds of quasi-news stories, or as quasi-journalism. I’ve always loved the story of William Eggleston’s Election Eve ( http://www.egglestontrust.com/election_eve.html ) – just before the 1976 election, Eggleston took an assignment from Rolling Stone magazine to photograph Jimmy Carter and his family in Carter’s very small hometown of Plains, Georgia. But when he arrived, Carter was out of town and on the campaign trail, so Eggleston just wandered around the outskirts of the town, photographing the surrounding fields, fences, mailboxes, barns, diners, gas stations, sidewalks, cemeteries, graffiti, flora, fauna and foliage. Of course, Rolling Stone never ran the pictures as there was absolutely nothing newsworthy or directly informative about them, but it became such a beautiful body of work that hums with the undertones of that particular time in history, that particular election, and what Carter represented and stood for in the context of the American cultural landscape. Perhaps SLANT – which was photographed between 2016-18, on trips to Amherst before, during and after the 2016 elections – takes a leaf out of Eggleston’s book in this regard.

BF: I want to get back to you about the idea of what occurs between the representations of the American landscape between East and West. You have alluded to a state of limited representation of the Eastern landscape by comparison to the West in the history of photography. As a mid-westerner I feel you, but then I start thinking about Bruce Davidson, Helen Levitt, Eugene Smith in Pittsburgh, Walker Evans over yonder in Bethlehem and I do not feel that perhaps the East is lacking in work or books being made, but perhaps that the urban centers are the problem. Just as the cavernous reaches of the canyons in the American West conquer the imagination with the mountains, perhaps our history of the Eastern landscape is quarantined to the city as landscape spectacle where concrete hinders our notion of what landscape is…

AS: Well, within the medium’s history many photographers who have attempted to address America as a whole begin their journey in New York – which is both south and west of New England – and head westward (or in some cases, southward). As a result, in photographic terms the East has generally become defined by the its urban and industrial centres – as you note, the factories, mills and mines of Pennsylvania or the “concrete jungle” of New York – and New England is often quite literally left out of the picture. Perhaps because of its colonial roots and historical ties to Europe (Amherst was first surveyed in 1665 by Nathaniel Dickinson, Emily’s great great grandfather, who came to Massachusetts from Lincolnshire, England, in his mid-thirties), New England, as its name implies, isn’t considered “American enough” in comparison with the West. But as the dedication at the beginning of Strand and Newhall’s Time in New England suggests (it reads, “To the Spirit of New England, which lives in all that is free, noble and courageous in America”), New England, including its rolling rural landscapes and “quaint” small towns, represents the foundations of America – historically, symbolically, ideologically and otherwise, for both good and bad. Mass immigration followed by anti-immigration and isolationist rhetoric; religious puritanism and fanaticism; encounters with, conquests over, and massacres of native peoples; westward expansion driven by both capitalist and colonial motives; transcendentalism and the romanticization of the natural landscape; the use of slave labor and the founding of fervent abolitionist movements; revolutions of independence and industrialization; the foundations of protest movements and labor unions; democratic philosophy and early notions of suburbia; and so on – all of these things took place first in New England. Massachusetts is named after a Native American tribe that was initially decimated by diseases brought to the continent by English colonists in the early 17thC., which was then forcibly converted to Christianity and resettled in ‘praying towns’, where they were expected to abandon their traditional religion, submit to colonial laws, and accept various aspects of English culture. The state motto of Massachusetts is, “By the sword we seek peace, but peace only under liberty”; the state motto of neighboring New Hampshire is more simply put, and perhaps more resonant in today’s political climate – “Live free or die.” Even Amherst itself is named after Lord Jeffrey Amherst, who as a British officer fighting in the so-called French & Indian War was one of the earliest colonists to advocate for the extermination of native populations via the gifting of blankets infected with smallpox. Within the popular imagination, many of these foundational principles, credos, convictions, doctrines, actions and atrocities are often situated in the myths and landscapes of the American West, but New England is really where it all started – again, for good and for bad – yet in the visual vocabulary used to define the country, photographically and otherwise, it’s often overlooked. Of course, SLANT only very quietly and indirectly nods to these various aspects of American history, mythology and culture (and more), which are firmly embedded within both its past and present throughout the country, but I hope that it will at least in part be read alongside other bodies of photographic work that address, examine, represent and reflect America at large – rather than being seen as a leafy, olde-worlde outlier within the context of America – even if the signs and symbols of this culture aren’t as seemingly blatant or brash as those that might be found in Las Vegas, Los Angeles, the Colorado Rockies, the Mississippi Delta, or other more well-tread regions.

……………………….

BF: There are a number of really humorous references in the text and the images that clearly have to do with our shared age. For example, the Delorean from Back to the Future is in the book, Space Invaders makes an appearance and then there are also annotations within the police reports about things like an unknown man trying to learn Seek and Destroy by Metallica. The corvette is also giving me T-Top and spoiler vibes. The use of vernacular and whimsical architectural “relic” such as the giant foot, the water slide to nowhere, the arrow on the lawn pinning the sod to the soil and the inclusion of many signs, strip club or other really pull the work back into an anachronistic state of play.

I remember at one point seeing a collage or an amount of 90s relics that you had in a notebook or in your mother’s attic. I remember the CKOne Mark Wahlberg and Kate Moss image. There was a pastiche of old letters and diary entries perhaps. You seem to keep a lot of items from your youth in both what you produce and what you assemble. How much of this work then becomes a personal examination of home and self? This work feels as though it is a collage of you. I feel as though you are excavating. I mean I bought a drum set, what are you doing to celebrate mid-life?

AS: On a very personal level, and looking at it retrospect, I think that at least part of this project represents a process of coming to terms with and trying to resolve my own nostalgia – for my childhood, for the late-twentieth century, and for the place where I spent it. When I got into photography as a teenager, I was so frustrated with being stuck in western Massachusetts. I would walk around, and eventually drive around, trying find things to take pictures of, but constantly saying to myself, “This place is so boring – there’s nothing to photograph here.” All I wanted to do was get to New York, where there were “interesting” people and “interesting” things to look at, and become a “real” photographer. But now, twenty-five years later, I’ve found myself returning to that same place and discovering a wealth of material that I find fascinating and both personally and generally relevant.

That said, throughout my twenties and thirties I was very aware that whenever I returned home to visit my parents, I always regressed a bit, both emotionally and behaviourly, and consciously sought out reminders of my youth in a romantic kind of way. I’d get in the car and drive around to old haunts – pizza places, cafes, bookshops, diners – while tuning into the college radio stations, or listening on the Pixies or Sebadoh or Dinosaur Jr. (all bands that formed in the area, locally known as the “Pioneer Valley”, in the ‘80s and ‘90s – think “U-Mass” by the Pixies: “In the sleepy West; Of the woody East; Is a valley full; Full o’ pioneer; We’ re not just kids; To say the least; We got ideas; To us that’s dear; Like capitalism; Like communism ; Like lots of things; You’ve heard about…It’ s educational…University; Of Massachusetts, please…Eeeed eeeed uuuuh caaaah tioooon!” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=59nUPJN6PPA) or even “Road Runner” by the Modern Lovers: “Roadrunner, roadrunner; Going faster miles an hour; Gonna drive past the Stop ‘n’ Shop; With the radio on; I’m in love with the modern world,; Massachusetts when it’s late at night; And the neon when it’s cold outside; I got the radio on…” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gy88-5pc7c8)).

“On a very personal level, and looking at it retrospect, I think that at least part of this project represents a process of coming to terms with and trying to resolve my own nostalgia – for my childhood, for the late-twentieth century, and for the place where I spent it. When I got into photography as a teenager, I was so frustrated with being stuck in western Massachusetts”

Even when I went back in 2015 with my own children, who were eight and ten at time, it was like getting into the Delorean with them and typing in 1985. Of course, some things have changed in the area in the last thirty years, but it’s remarkable how much has stayed the same in many ways, and how easy it was for us to return to my childhood experiences and patterns without much effort – they could eat at the same ice-cream shop I did as a kid, go to the same playgrounds, wander around the same shops downtown; a lot of it’s still there. In an old railway building just outside of Amherst we even found a hipsterfied “retro” arcade with “vintage” arcade games – The Quarters (https://hadleyquarters.com) – and I swear the owners must have simply gone to the now mostly defunct or “dead” mall that I went to as a kid, and pulled out the same machines that had probably been in storage since 1993 – they were all there: Pac-Man, Space Invaders, Donkey Kong, Rampage, Arkanoid, NBA Jams and so on.

But as you note, while I was making this project I also hit the age of forty, the gap between my present and that past was ever-widening, and I became much more self-conscious of the fact that these internal regressions into adolescence, although still amazingly comforting, were starting to feel somewhat ridiculous, a bit self-indulgent and slightly pathetic. I’d walk into a coffee-shop where I used to spend hours as a sixteen-year-old reading or hanging out with friends or trying to meet sophisticated college girls, look around at all the students with their flat-whites staring at their laptops, and realize that many of the memories that flooded over me when I first stepped into the place had occurred well before most of the people in room had even been born. Furthermore, in the process of making photographs and reading the police reports, and considering what they were quietly insinuating about the psychological, cultural and political undercurrents of contemporary times, my rose-tinted teenage idea of the place where I grew up was gradually being dismantled and redefined through a more mature lens.

I hadn’t really thought about this before, but Back to the Future (1985) is an interesting reference. Watching it back today, it’s pretty problematic in a number of ways, particularly in terms of how it reflects the predominant American value systems of the 1980s, but it’s particularly relevant to SLANT in terms of how it depicts variations of Marty McFly’s hometown. The 1985 version of “Hill Valley” is relatively functional but slightly run down – there trash and graffiti scattered about, the downtown has florists and aerobics studios but also bail-bondsmen and abandoned storefronts, the old movie theatre screens pornos, another art-deco theatre has been converted into an evangelical church, there’s a homeless man sleeping on a bench under a pile of newspapers, and of course the clock-tower has been broken and left derelict for thirty years (oh, and there’s rampaging Libyan terrorists screeching past JCPenney and through the mall parking lot to boot). Alternatively, the 1955 version of the town is a thriving all-American, mid-twentieth-century Happy-Days-like idyll, with teenagers holding hands and sipping milkshakes at the shiny chrome-lined diner, and Chuck Berry playing the sock hop. In a sense, in making SLANT, I was also personally negotiating the territory between the nostalgic, “innocent”, idyllic child-like fantasy I had of a particular place and my conflicting contemporary experience and newfound understanding of it, and of America at large.

For example, more than fifteen years ago I took a photograph of an old tobacco barn in the area that, ever since I’ve known it, has been covered in graffiti – Bobby ♥ Sue, etc. In my original early-2000s photograph (which I included in the first ever issue of SeeSaw Magazine – http://seesawmagazine.com/winter_pages/hear_the_music.html ) the graffiti is mainly romantic lyrics from Led Zeppelin’s Stairway to Heaven – “IF THE SUN REFUSED TO SHINE, I WOULD STILL BE LOVING YOU”. During my trip back to western Mass in 2018 for SLANT, I suddenly remembered this barn, and spent an hour or so driving up and down back roads trying to re-find it. Eventually, I saw it on the horizon still covered in graffiti, but as I approached I realized the tone of much of the graffiti had significantly changed – it now read, “IN BORDER PATROL WE TRUST”.

BF: Of course this opens the gate for large topics dwelling on time and meaning, representation and event, but also the current climes of fear in which we find ourselves lamenting over “otherness” not too far distant from the future we were promised with the hover boards that never happened.